In our last article, we outlined how the electoral college works. What happens, though, if no one wins a majority? Can that happen?

The electoral college requires that a candidate win a majority of votes, not just the largest number of votes. Where there are only two realistic candidates for the office, that does not pose a problem. A tie at 269 electoral votes each is not likely to happen. What if there is strong third party candidate? That candidate could win some electoral votes. If that happens it might be that no one gets a majority (the magic 270 number).

The electoral college votes are cast in state capitols in December. After an election, on January 6, the ballots are opened and counted in front of a joint session of Congress.

Selecting the President in the House of Representatives

If no one gets a majority of the electoral college votes for President, the election moves to the House of Representatives. The Constitution says that the House will “immediately” choose the President in such a case. The House cannot select its own candidate for president. Instead, the House musty choose from the top three candidates from the electoral college vote.

This procedure is not like the normal procedure for passing laws. Instead, each state gets one vote in the House. Each state’s delegation (the elected representatives from that state) will get together and decide how to vote. For example, Nebraska has three members of the House of Representatives. They would meet and decide how to cast Nebraska’s vote for President. Nebraska would then cast one vote. Every other state’s delegation would do the same thing. To select a President, the majority of states must agree on a President. With 50 states, that means 26 state delegations must agree on who will be president.

What if no one wins in the House? The House may go through multiple rounds of voting in order to select a President. The House must choose a President before January 20 when the Presidential term begins. If the House misses the deadline, the Vice President elect acts as President until the House can select a President.

Selecting the Vice President in the Senate

If no one gets a majority of the electoral college votes for Vice President, the election of the Vice President moves to the Senate. The Senate must choose from the top two candidates from the Electoral College vote.

When the House has to select a President, each state gets one vote. When the Senate has to select a Vice President, each state gets two votes. Each senator gets one vote. A candidate for Vice President must be selected by a majority (today, 51 or more) of the Senators. The sitting Vice President is the President of the Senate and can cast a ballot to break a 50-50 tie.

These rules make sure that the Senate is always able to select a Vice President elect. Even if the House is divided on selecting a President, these rules guarantee that a Vice President elect can be selected. This assures that someone can always be empowered to act as President.

Old or New Congress to Select President and Vice President when Electoral College Can’t?

One-third of the Senate and all of the House of Representatives are elected at the same time a presidential election is held. Is it the newly elected members of Congress that make the decision or the old Congress that makes the decision? The new Congress convenes (by Constitutional mandate) on January 3, unless they by law move that date. The electoral college votes are counted on January 6. Since the new Congress would be sworn in before the electoral college votes are counted, the newly elected Congress selects the President and Vice President if the electoral college vote fails. This has not always been true, and in 1800, it was the “old” House of Representatives that selected the President.

What Has Or Could Happen?

What if the Senate and House of Representatives are controlled by different parties? If that happens and the votes for President and Vice President reflect party loyalty within the Congress, it would be possible to have a President and Vice President of different parties.

Has the House of Representatives ever selected the President? Yes, twice, in 1800 and 1824.

1800 Presidential Election

Following the ratification of the Constitution, presidential elections were held in 1788-1789, 1792, and 1796. George Washington won the first of those two elections, and John Adams won in 1796. In 1800, Adams ran against Thomas Jefferson. They were bitter rivals. Ultimately, this election marked the first transition of power from one political party to another. The aftermath of this presidential election helped form the fundamental structure of American government. As part of that, it revealed a structural flaw in the electoral college process.

The electoral college worked differently in 1800, and each elector cast ballots for two people. They did not cast a vote for president and one for vice president; instead, they simply voted for two people. The winner would become President if he had received a number of votes equal to the majority of the number of electors.

In 1800, there were 138 electors, so 70 votes would have to be cast for someone to become President. Jefferson and his vice-presidential running mate were tied at 73 votes each. A plan to coordinate electors’ votes to assure that Jefferson got one more vote than Burr failed.

Since both men had a majority and they were tied, the House of Representatives had to choose between Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr. Many of the state delegations were controlled by Federalists who refused to vote for Jefferson and voted for Burr instead. Some delegations initially abstained. No one got a majority until Alexander Hamilton convinced fellow Federalists on two delegations that Jefferson was preferable to Burr – on the 36th ballot!

The election of 1800 led to the Twelfth Amendment where President and Vice President were selected individually by electors. This was to prevent a repeat of the 1800 debacle. We have used this revised system since then.

1824 Presidential Election

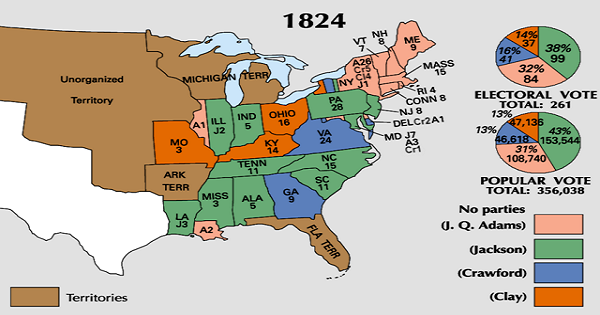

In 1824, four candidates running for President received votes in the electoral college. The House of Representatives, then, had to decide from among the top three candidates from the electoral college. These candidates were Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and William H. Crawford.

Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House, was the fourth candidate for President who had won electoral college votes. Because the House had to choose from the top three in the electoral college vote, Clay was eliminated from consideration. Clay disliked Jackson and threw his support behind Adams. Adams was selected by the House on the first ballot, unlike the 36 ballots the House took in 1800.

Jackson, who had won the popular vote in the states that had a popular vote for President, was furious, claiming a “corrupt bargain” had been struck between Clay and Adams. In 1828, there was a rematch between Jackson and Adams, with Jackson being elected President.

Durability

The Framers of the Constitution put together a process to select the President that assured each state would have input into the process. They designed backup mechanisms to take over if the electors failed to select a President. When those mechanisms proved to be flaws in the 1800 election, the process was reformed. The system now provides a durable process to assure the office of President is filled following even contentious elections. In a final article in our series on the electoral college, we will explore why we would want this system.