On April 2, President Trump announced a sweeping regimen of tariffs. Tariffs used to be more prominent – both as a revenue source and as a direct impact on Americans. Here we address what a tariff is, who pays it and the risks and opportunities they present.

Before 1913, there was no national income tax. While a few attempts had been made to impose one, those efforts had been struck down as unconstitutional. Creating an income tax required approving the Thirteenth Amendment, authorizing an income tax. Prior to this, national government revenue was came primarily from tariffs and other taxes imposed on foreign trade. Since 1913, income taxes have become the primary revenue source for the national government.

What is a Tariff?

A tariff is a tax on a product as it crosses national borders. It is slightly different than a sales tax in that a sales tax is due when something is sold; a tariff is due when a product crosses a national border even if it is not sold at the same time. There can be either export or import tariffs. In an export tariff, the country the product is leaving collects the tax as the product leaves. Typically, however, we are referring to import tariffs in which the country receiving the product collects the tax.

As a mechanism of collecting a tariff, the company importing (or exporting) the product delivers the required amount to the government. As we shall see below, who is actually paying the cost of a tariff is somewhat more complicated.

Who Pays Tariffs?

To illustrate who really pays a tariff, we need to understand that there are many transactions to get a product from one company to another. The many parties to those transactions may all be impacted by a tariff on the product.

Without Tariffs

The chain of events for a product may look something like this. We consider the hypothetical journey of a widget. Some products may have more hands touch them than this; some may have fewer. This should allow us a good illustration to explore who pays for tariffs.

- A manufacturer in a foreign country builds the widget and sells it for $500

- An importer in the United States buys the widget and pays $25 to get the widget shipped, for a total cost of $525.

- The importer sets a price of $600.

- The importer has a profit of $75 per widget.

- A domestic distributor buys the widget from the importer for $600.

- The distributor has costs of $25 per widget to get it where it is going

- The distributor sets their price at $675

- The distributor has a profit of $50.

- The retailer sells the widget to a consumer for $750

- The retailer has a profit of $50.

Note that the “profits” here are ignoring costs other than the cost of the product itself. Actual profit after including other expenses would be lower, but we want to keep the illustration as simple as possible,

With Low Tariffs

Once the United States imposes a tariff on the imported widget, the costs of that tariff are typically spread across everyone from the importer to the ultimate customer.

With a low tariff, it is possible that the entire cost will be born very early in the supply chain. Consider a 2% tariff. The widget comes in at a price of $500 with no tariff. A 2% tariff would be a cost of $10 based on the $500 price.

The manufacturer may decide to reduce the price of the widget to $490.20. Now, the price to the importer is $490.20, plus a tariff of $9.80. In this scenario, the manufacturer has born the cost of the tariff. A rational manufacturer might do this to maintain market share. This only works, of course, if the manufacturer has a larger profit margin than the tariff. A manufacturer with a much more narrow profit margin may accept some of the cost, but not all of it.

Low tariffs are likely to be born by the different parties in the distribution channel with little or no impact on the consumer

With High Tariffs

With a high tariff, we will probably see something different. Most of the parties will probably absorb some of the cost of the tariff. Some of the cost often falls on the end consumer. Revising our original flow, we might have a scenario like the following. For this illustration, assume we have a 10% tariff.

- A manufacturer in a foreign country builds the widget and wants to sell it for $500.

- The manufacturer reduces the price to $495 to help preserve market share.

- The manufacturer bears a $5 cost.

- An importer in the United States buys the widget for $495 and pays $25 to get the widget shipped, for a total cost of $520.

- The importer must now pay $49.50 (10% of the reduced widget price) to the government as the tariff, raising the importer’s cost of the widget to $569.50.

- The importer adjusts the price from $600 to $635, passing along a lot of the cost of the tariff.

- The importer bears $10 of the tariff, as their profit falls from $75 to $65.50.

- A domestic distributor buys the widget from the importer for $640

- The distributor’s cost is now $685 (the $640 widget price, plus the original $25 shipping cost)

- The distributor raises their price from $675 to $720

- At the new price of $720, the distributor has a profit of $35, versus $50 without the tariff

- The distributor has paid $15 of the tariff, through reduced profit

- The retailer buys the widget for $720

- The retailer applies the same $50 markup as they had without the tariff

- The retailer is paying none of the tariff, which we would expect given usually low profit margins at the retail level.

- The retailer sells the widget to a consumer for $770.

- The consumer has paid an extra $20 due to the tariff.

Note that this is a hypothetical example only. How much the different actors will change their prices depends on a wide variety of factors.

Why Don’t End Customers Typically Pay the Full Cost of a Tariff?

In some cases, the entire cost of a tariff could be passed on to the consumer. This is most likely to happen if the price of the product is very low (compared to the consumer’s income), profit margins through the supply chain are low, the product is very important to its consumers, and there are few substitutes the consumer could use instead.

In a typical case, though, there are often higher profits, or readily available substitutes. The manufacturer wants to to keep building the product. A somewhat smaller profit per item sold is an acceptable adjustment to keep things running. The importer may not be willing to continue buying a tariffed product without price concessions from the manufacturer.

At each step of the distribution channel, there is someone selling the widget and someone buying the widget. The seller typically wants to pass on the higher costs to the buyer. The buyer wants to reject the increased price of the widget. These conflicting interests at each stage lead to negotiations, which will typically lead to some sort of cost sharing, spreading the burden of the tariff throughout the entire distribution channel.

A seller cannot force a buyer to accept a higher price. To stay in business, the seller must often accept prices that do not fully pass on tariff costs. The net effect of this reality is spreading the tariff cost across the many parties involved in getting the product from the factory to the end consumer.

What are the Purposes of Tariffs?

Tariffs serve a few purposes.

Revenue

Tariffs may generate revenue for the government. In this sense, they are similar to a sales tax. To make tariffs effective as a revenue generation tool, tariff rates must be relatively low. If tariffs are too high, imports will become too expensive. End customers will find other goods to use instead. As customers make that shift, tariff revenue will fall, since the number of goods coming across the border declines.

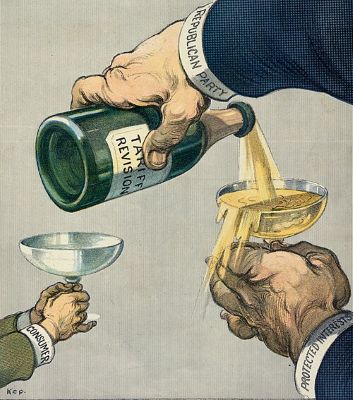

Protection

Tariffs may be used to “protect” domestic industries. This use of tariffs is intended to deliberately drive up the cost of foreign products to convince consumers to use domestic alternatives. The general argument for this is to protect domestic jobs. There may also be some domestic industries which need to remain strong for national security reasons.

Protectionist tariffs need to be relatively high in order to force the desired change in consumer behavior to patronize domestic industries. While protectionist tariffs may generate some revenue, the revenue they bring in will be relatively low if they are effective at their protectionist goal. Industrial groups and labor unions in manufacturing often support protectionist tariffs.

Bargaining Leverage

The third major argument for tariffs is that they can be used as leverage in negotiations with other countries. Tariffs create a bargaining chip. For instance, the United States might impose a tariff on Japanese cars because Japan does not allow American cars into Japan. The bargaining position, then, would be “we will tariff your cars so much that you can’t sell them in America until you change your rules, so we can sell our cars in Japan.” While people who support free trade (relatively unrestricted movement of goods across national boundaries) would oppose protectionist tariffs, they often are willing to accept tariffs as bargaining chips when used to help open up markets to freer trade.

Conclusions

Tariffs can be useful tools to serve different purposes. The same tariff, though, typically cannot serve more than one of those purposes. An effective protectionist tariff cannot be an effective revenue tariff, and vice versa. A bargaining chip tariff can be neither protectionist, nor long-term revenue-generating, as you must be willing to give it up as part of the negotiations.

Foreign trade generally benefits most countries involved in it. Excessive tariffs hurt that, ultimately to the harm of everyone. This often comes about as protectionism takes hold with countries trying to out-tariff each other.