This weekend, we celebrate Labor Day. Labor Day signals many things. What was it originally about, though, and why are we celebrating?

A shift in the American economy from an agrarian base to an industrial base was well underway by the mid 1800s. Nowhere in the world was that transition painless, and the United States was no exception. Anyone familiar with Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, or many of his other works, can see a glimpse of the social upheaval of this transition as it happened in London.

Early Labor Movement Environment

Working conditions in new factories were often brutal and unsafe. This drove a movement toward unionization. When workers formed unions, they engaged in collective bargaining. Union negotiators would bargain with the employer to get improvements in working conditions and wages.

Today, there are laws that protect workers’ ability to join together and form unions. Early on, those laws did not exist. Early on, labor disputes often became violent. Unions often included agitators promoting violence against companies. In turn, companies often tried to replace union members with non-union workers. Companies often retaliated hiring private “detective” agencies to infiltrate and suppress, at times violently, union activity.

Creating Labor Day

As the union movement grew, supporters wanted to set aside a day to celebrate the movement and the American worker. It is disputed as to who actually had the idea for a holiday first.

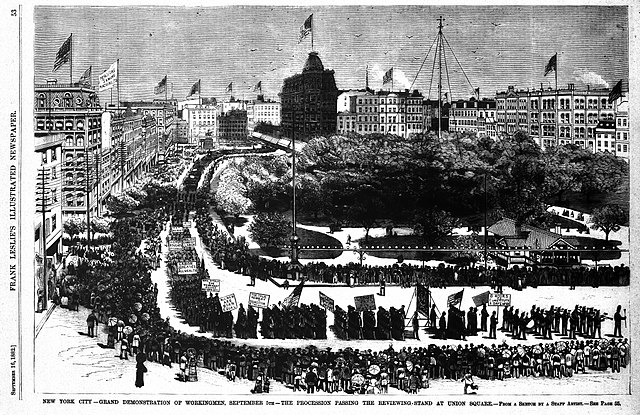

One account says that Central Labor Union secretary Matthew Maguire first proposed a holiday to be on the first Monday in September. This followed a parade by various labor organizations in New York City in September 1882.

Another account focuses on Peter McGuire, the Vice President of the American Federation of Labor. According to this account, McGuire visited a parade in May of 1882. In much of the world, workers are celebrated on May Day (May 1), explaining the Toronto parade in 1882. McGuire envisioned a day celebrated with parades celebrating the union movement, culminating in a picnic. He proposed the first Monday in September as ideally situated between the existing Independence Day and Thanksgiving holidays.

The first Labor Day celebration was on September 5, 1882, in New York City. The event centered around a parade through lower Manhattan. It included musicians, flags, and all the things that would be expected for a major celebration parade. Police were present in force, prepared for a riot, though none developed. Estimates for attendance at the spectacle range from 10,000 to 20,000. As McGuire envisioned, the parade culminated in a picnic and speeches with additional unions showing up for the post-parade activities.

Following the New York parade in 1882, the idea spread to other places. Before 1894, at least 34 states were officially celebrating Labor Day. Municipal ordinances passed in 1885 and 1886 in some places began to establish an official holiday. In 1887, Oregon was the first state to create an official public holiday. On June 28, 1894, President Grover Cleveland singed a bill into law that created an official federal holiday.

The 1894 law only provided a holiday for federal workers. Union advocates continued to push for a general holiday. They even advocated strikes for workers to get the day off.

Labor Day Today

Today, Labor Day largely marks the end of the Summer season. Summer activities are generally seen as running from Memorial Day in May to Labor Day in September. Fall activities, such as schools and several professional sports typically start after or near Labor Day.

Rather than attending parades, Americans today typically celebrate Labor Day with barbecues and other family activities. Many businesses remain open on Labor Day.

A variety of safety and wage protections have been written into law over the last century. With that and some controversy about union tactics and political involvement, union membership has shrunk considerably from what it once was. A relative shift from industrial work to more service work has also tended to diminish union membership. The holiday remains, however.

Whatever one may think of the union movement, the American worker is deserving of recognition. Without the hard work of those who get up every day and go off to their jobs, we would not have the safety and conveniences of our daily lives.

Today, we tip our hats to the American worker.