In common political discussion today, we often hear candidates described as left-wing or right-wing. We speak of a left-right political spectrum. Where did those terms come from, though? Do we use them correctly, and are we at all correct about who is left and who is right?

One thing that is important to political discourse is to have some agreed upon terms to use. The so-called left-right political spectrum is perhaps one of the most misused. We will begin by looking at the origins of the left-right spectrum. We will then briefly consider whether some popular political perspectives are right or left. Our presentation will necessarily be brief, yet we hope it will be illuminating in the limited space we have. Finally, we will consider whether or not the left-right spectrum is useful.

Origins of the Left-Right Political Spectrum

An obvious question might be how a direction, such as left or right, should represent political beliefs? The answer is as basic as a seating chart.

The Estates General

In the early 14th century, the Estates-General was established in France. It acted as an advisory body to the French monarchy. In advising the monarch, it provided a way to represent the three classes (or estates) recognized by the French political system. These classes were the clergy (the First Estate), the nobility (the Second Estate), and the commoners (the Third Estate). Today, we sometimes hear reference to the media as the fourth estate, going back to this French institution.

The Estates General met periodically up until the early 17th century. It then did not meet again until the period of the French Revolution in 1789.

A system of French Parlements dates to the 14th century. These bodies were powerful judicial bodies, though they had power over taxation as well. The most important of the Parlements was in Paris. In August 1788, the Parlement of Paris refused to reform taxes or extend a loan to the Crown. At that time, the royal treasury was empty.

The financial state of the French government paved the way for chaos. To try to address this problem, the Minister of Finance called for a meeting of the Estates General to resolve the severe fiscal problems.

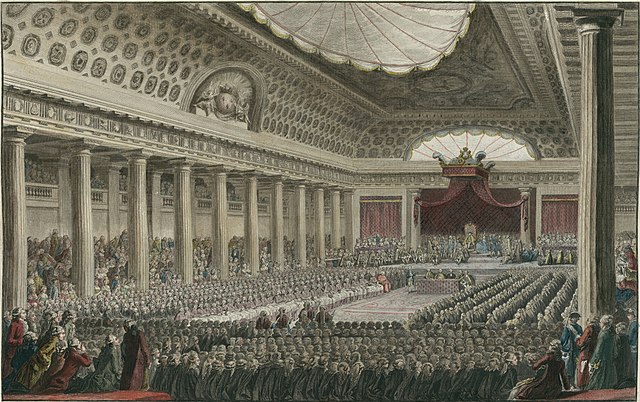

In 1789, the First Estate was composed of about 100,000 clergy. The Second Estate was composed of about 400,000 nobility, and the Third Estate was about 25 million commoners. The Estates General met in Versailles on May 5. Though the Third Estate had twice the number of delegates, votes were taken by Estate, so the 25 million commoners had only one vote, while the clergy and nobility each also had one vote.

Formation of the National Assembly

Understandably, the Third Estate did not like having their voting power diluted. Not only that, only the Third Estate would be paying any taxes that were levied. The deck was clearly stacked against them. Efforts to change the rules and structure of the Estates General failed. In protest, they left the Estates General and met independently. They initially called themselves the Commons.

Once the Commons organized themselves, they invited the other two estates to join them. They also defined what their powers would be. Eventually, the Commons was renamed to the National Assembly. King Louis XVI tried unsuccessfully to shut down the National Assembly. When he tried to block access to their meeting place, the assembly moved to a tennis court. There, they took the Tennis Court Oath, vowing to not disband until they had crafted a French Constitution.

Support grew around France for the National Assembly. Some members of the First and Second Estates joined the assembly. The monarchy gave up resistance. In early July, the body renamed itself to the National Constituent Assembly. After Paris mobs stormed the Bastille prison on July 14, 1789, royal power had largely collapsed. Royal commands were no longer regularly obeyed. The French Revolution was well underway.

The National Constituent Assembly

The stated purpose of the assembly was to create a French Constitution. One of the key issues to be resolved for that was the role of the monarchy in a new French government. Members of the assembly represented a very broad range of opinions about the role of the monarchy. Some sought to restore the monarchy. Some sought to establish a limited monarchy like the constitutional monarchy that had already evolved in England. Yet others sought an abandonment of the monarchy altogether and varying forms of democratic government.

The members of the assembly tended to gather themselves together with like-minded people. For instance, those supporting the monarchy tended to group with other monarchists. Those supporting democracy tended to group with others supporting democracy. The general seating at the National Constituent Assembly thus evolved so that those who sought to restore the monarchy were sitting at the speaker’s right, and those seeking democratization sought at the speaker’s left.

This pattern of seating by faction led to references to the left or the right. Sitting by faction is common as well today. For instance, in the U. S. Congress, members sit on one side or the other on the floor of the House or Senate based on party affiliation.

On the Right of the Political Spectrum

Delegates on the right tended to support maintaining traditional political structures. The most stringent of these favored a return to the previous monarchical regime. Today, we might also refer to those seeking to return to an earlier regime as reactionary. Less stringent delegates on the right might support incremental reforms, even those which would shift power away from the monarchy toward a system more like that of England.

In addition to preserving political structures, those on the right will tend to support preservation or gradual evolution of other social structures. These would include things like the church and the role of religion in society.

While reactionaries may want to roll back major social structures, conservatives will tend to advocate organic evolution of social structures.

On the Left

Delegates in the assembly that advocated a shift to democracy were radicals. Radicals seek to make significant breaks in social structures. This is based not on evolutionary learning of society, but rather on a rationally-conceived significant reworking of social structures. While ideologies of the right have faith in accumulated societal knowledge expressed in tradition and mores, ideologies of the left have faith in the ability of individual human reason to successfully identify preferable new social structures even if they are unlike institutions previously experienced.

In 1789, calls for democratic structures, informed by writers such as French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, would have been radical. Classical liberalism as expressed by the mid to late 17th century writings of English philosopher John Locke would be less extreme and perhaps somewhat center-left.

It is worthwhile to note that classical liberalism with its emphasis on natural rights (to life, liberty, and property) and a social contract basis for government drove the radicalism of the American Revolution. It was a radical ideology at the time. Classical liberalism, however, is a key part of the American tradition. This means that American conservatism (on the right) seeks in part to preserve some of the values of classical liberalism (a once-radical ideology that would definitely be seen as right of center today).

Anarchism and all flavors of socialism (including communism, democratic socialism, and fascism) are to one degree or another radical ideologies and, therefore, properly regarded as ideologies of the left. To varying degrees, these ideologies developed after the French Revolution.

Limitations of the Spectrum

The left-right political spectrum has some significant limitations for categorizing political ideologies. The left-right dimension is really a range from radicalism on the left to traditionalism on the right. There are other key elements we might want to consider.

For example, fascism is often (errantly) discussed as a right-wing ideology based on its nationalism. This ignores its growth out of socialist intellectual circles and even many fascists’ explicit embracing of socialism. Why would nationalism be a more important factor than fascism’s radicalism in determining placement on a left-right spectrum? More importantly, there is not a necessary correlation between nationalism and traditionalism or nationalism and radicalism.

Further, recognizing anarchy and socialism as left-wing ideologies does not tell us anything about the differences between anarchism and socialism or even differences among different conceptions of socialism. It seems important that we consider other aspects of political ideologies when creating categories. For example beyond the traditionalist-radical dimension, we might want to consider a nationalist-internationalist dimension or a collectivist-individualist dimension.