As we approach Independence Day next month, but what led to the Declaration of Independence in the Continental Congress? Here, we look at the Lee Resolution and how it drove us to independence.

Revolutionary Sentiment Builds

In April 1775, the Battle of Lexington and Concord launched the Revolutionary War. American revolutionaries seized Fort Ticonderoga in May, and the Battle of Bunker Hill boosted American resolve in June. In July, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution called the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. This document sought to explain why the colonies had taken up arms against Great Britain.

The Olive Branch Petition was sent to King George III in a last-ditch effort to stop escalation of the conflict in July only two days after the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms was adopted. In response to the Battle of Bunker Hill, on August 23, King George III issued A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition (commonly referred to as the Proclamation of Rebellion).

Attempted and Abandoned Reconciliation

Colonial efforts to avoid further escalation continued through the end of 1775, even as more battles were being fought by the new Continental Army. In December of 1775, Congress issued a response to the Proclamation of Rebellion. In this document, the colonials professed loyalty to the King, claiming their dispute was with Parliament. They argued that Parliament had violated the British constitution and exceeded its power in the way it treated the colonies. George III showed no inclination to act as a moderator between the colonies and Parliament.

On January 10, 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense. In this pamphlet, Paine argued that it did not make any sense that an island nation so far away should be ruling North American colonies. Paine’s pamphlet helped to grow support for a final break with Great Britain. Continuing military conflicts further pushed colonial sentiment toward independence.

Lee Resolution Introduced

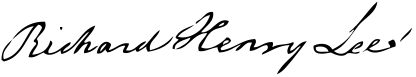

On June 7, Richard Henry Lee, a delegate to the Continental Congress from Virginia, introduced what we now know as the Lee Resolution. This resolution

- declared the American colonies to be free of Great Britain

- called for forming a plan to form alliances with other nations

- called for a plan for a new confederation of the American colonies to be formed

In full, the resolution reads as follows.

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

Consideration of the Lee Resolution

While there was strong sentiment for independence, there was also opposition. Some believed that the resolution was premature, as they held out hope for a reconciliation with Great Britain. A significant portion of the colonial population was also still generally loyal to Great Britain and simply opposed breaking from their homeland.

Because of these reservations and the desire of some delegates to get instructions from their colonies before voting, Congress decided to wait to vote on the Lee Resolution until July 2, 1776. On that date, twelve colonies voted in favor of the Lee Resolution. New York abstained, awaiting instructions from their colony.

While the resolution was not adopted until July 2, Congress did take related actions earlier than that. On June 11, Congress formed three committees

- to draft a Declaration of Independence

- to form a plan for forming alliances with other nations

- to prepare a plan for a new confederation for the thirteen colonies about to declare themselves independent

The committee to draft a Declaration of Independence included John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert L. Livingston. Jefferson emerged as the main writer of the document. Today, we credit him as the author of the Declaration of Independence approved by Congress on July 4, 1776.

A Cause for Celebration

On July 3, following adoption of the Lee Resolution, John Adams wrote the following to his wife

[While a declaration of independence months earlier would have been glorious,] the Delay of this Declaration to this Time, has many great Advantages attending it. — The Hopes of Reconciliation, which were fondly entertained by Multitudes of honest and well meaning tho weak and mistaken People, have been gradually and at last totally extinguished. — Time has been given for the whole People, maturely to consider the great Question of Independence and to ripen their judgments, dissipate their Fears, and allure their Hopes, by discussing it in News Papers and Pamphlets, by debating it, in Assemblies, Conventions, Committees of Safety and Inspection, in Town and County Meetings, as well as in private Conversations, so that the whole People in every Colony of the 13, have now adopted it, as their own Act. — This will cement the Union, and avoid those Heats and perhaps Convulsions which might have been occasioned, by such a Declaration Six Months ago.

But the Day is past. The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epoch, in the History of America.

I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

Ultimately, we would come to celebrate adoption of Jefferson’s Declaration two days after adoption of the Lee Resolution. As we celebrate Independence Day in just a few weeks, let us do so with the enthusiasm foreseen by John Adams. Let us further do so with gratitude for those who were willing to risk all those many years ago.