We previously wrote about the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Today, we present, a message from Massachusetts to the people of Great Britain a week after the battle – Joseph Warren’s Letter of April 26, 1775. Hostilities had certainly begun, and the battle intensified the grievances against Great Britain. Despite that, there was also some sentiment that a resolution could be reached without additional violence.

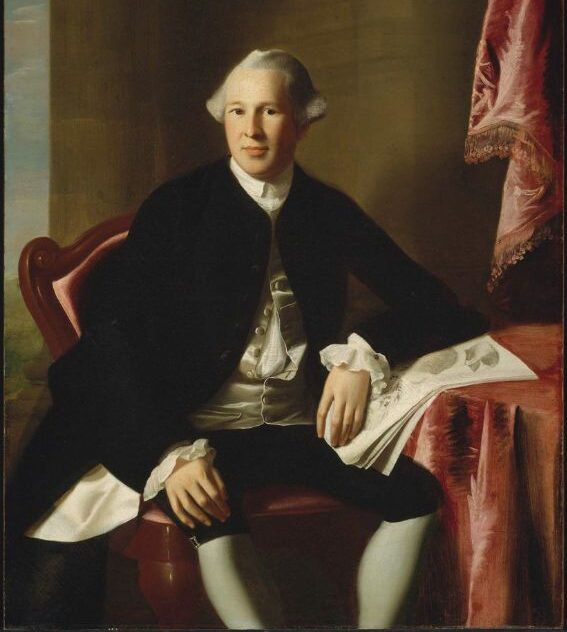

The message we consider here was given by Dr. Joseph Warren on April 26, 1775. At the time, Dr. Warren was the President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

We have slightly altered the text for the benefit of modern audiences. We have replaced the older “ye” with “the” and replacing “&” with “and.” While capitalization and spelling differ from English today, we have generally left as it was, except where the variations might be unclear to today’s reader. We identify all instances of alteration are noted with square brackets around any substituted language.

We have also broken the speech into paragraphs and broken a list presented in narrative form into a numbered list with the text preserved. Headers breaking up the text are additions for the benefit of the reader.

A transcript of the original language can be seen here, from the National Archives.

Joseph Warren’s Letter

In provincial Congress

Watertown April 26th 1775

To the Inhabitants of Great Britain.

Friends [and] Fellow Subjects,

Hostilities are at length commenced in this Colony by the Troops under Command of General Gage, [and] It being of [the] greatest Importance, that an early, true, [and] authentic account of this inhuman proceeding Should be known to you; the Congress of this Colony have transmitted [the] Same, [and] from want of a Session of [the] [honorable] continental Congress think it proper to address you on [the] alarming Occasion.

The Facts of the Battle

By the clearest Depositions relative to this Transaction, It will appear, that

[1] on [the] Night preceding [the] nineteenth of April instant, a Body of [the] Kings Troops under Command of [Colonel] Smith were secretly landed at Cambridge with an apparent Design to take or destroy [the] military [and] other Stores provided for [the] Defence of this Colony, [and] deposited at Concord

[2] that Some Inhabitants of [the] Colony on [the] Night aforesaid, whilst travelling peaceably on [the] Road between Boston [and] Concord were seized [and] greatly abused by armed Men, who appeared to be Officers of General Gage’s Army

[3] that [the] Town of Lexington by these Means was alarmed, [and] a Company of [the] Inhabitants mustered on [the] Occasion

[4] that [the] regular Troops on their Way to Concord marched into [the] said Town of Lexington, [and] [the] said Company on their approach began to disperse

[5] that, notwithstanding this, [the] Regulars rushed on with great Violence [and] first began Hostilities by firing on said Lexington Company, whereby they killed eight [and] wounded several others [and] that [the] regular continued their Fire untill those of said Company, who were neither killed nor wounded, had made their Escape

[6] that [Colonel] Smith with [the] Detachment then marched to Concord, where a Number of provincials were again fired on by [the] Troops, two of them killed [and] Several Wounded, before [the] provincials fired on them [and] that these hostile Measures of [the] Troops produced an Engagement that lasted [through] [the] Day; in which many of [the] provincials [and] more of [the] regular Troops were killed [and] wounded.

British Abuses

To give a particular account of [the] Ravages of [the] Troops as they retreated from Concord to Charlestown, would be very difficult, if not impracticable; let it suffice to say, that a great Number of [the] Homes on [the] Road were plundered [and] rendered unfit for use; Several were burnt; Women in Child-Bed were driven by [the] Soldiery naked into [the] Street; old Men [peaceably] in their Houses were shot dead; [and] such Scenes exhibited, as would disgrace [the] Annals of [the] most uncivilized Nation.

These, Brethren, are Marks of ministerial Vengeance against this Colony, for refusing with her Sister Colonies a Submission to Slavery; but they have not yet detached us from our royal Sovereign: We profess to be his loyal [and] dutiful Subjects, [and] so hardly dealt with as We have been, are still ready with our Lives [and] Fortunes to defend his person, Family, Crown [and] Dignity. Nevertheless, to [the] persecution [and] Tyranny of his cruel Ministry We will not tamely Submit – appealing to Heaven for [the] Justice of our Cause, We determine to die or be free.

On Course to Ruin the Colonies and Great Britain

We cannot think that [the] Honour, Wisdom, [and] Valour of Britons will suffer them to be longer inactive Spectators of Measures, in which they themselves are so deeply interested – Measures pursued in Opposition to [the] Solemn protests of many noble Lords, [and] [expressed] Some of conspicuous Commoners, whose Knowledge [and] Virtue have long characterized them as some of [the] greatest men in [the] Nation – Measures executing contrary to [the] Interest, Petition [and] Resolves of many large respectable [and] opulent Counties, Cities [and] Burroughs in Great Britain – Measures highly incompatible with Justice, but still pursued with a Specious pretence of curing the Nation of its Burthens – Measures, which if successful, must end in the ruin [and] Slavery of Britain as well as [the] persecuted American Colonies

Appeal for British People to Encourage Change

We sincerely hope that [the] great Sovereign of [the] Universe, who hath So often appeared for [the] [E]nglish Nation, will support you in every rational [and] manly exertion with these Colonies, for saving it from ruin, [and] that, in a constitutional Connection with [the] Mother Country, We Shall soon be altogether a free [and] happy people –

Per Order Jos Warren

Taking this as a representation of American (or at least Massachusetts) sentiment about the Battle of Lexington and Concord, we notice a few things.

Joseph Warren’s Letter’s Key Observations

Hostilities Responsibility of Britain

First, Warren recognizes that hostilities have started between American colonists and Great Britain. More important, though, is the declaration that the action was “inhuman.” Clearly, Warren is accusing the British Army of atrocities, or what we might call war crimes today. While some of this may be seen as exaggeration, it is important to note that such accounts found receptive ears at least within Massachusetts.

Second, Warren places blame for starting hostilities clearly on the British. He claims that the British fired first at Lexington and therefore are responsible for what followed throughout the engagement. It is worth noting that post action reports by British Colonel Smith and General Gage claim that the colonists fired the first shot. In general, historians today say that we really have no idea who fired first. Some even suggest that the first shot may have come from a bystander on the edge of the Lexington Green.

Omits Colonial Attacks on Withdrawing Troops

Third, while the British after action accounts note the harassment of the British as they withdrew to Boston, Warren notes only atrocities said to be committed by the British. General Gage’s report noted that colonial fighters

fired again as before, from all Places were they could find Cover, upon the whole Body, and continued so doing for the Space of Fifteen Miles: Notwithstanding their Numbers they did not attack openly during the Whole Day, but kept under cover on all Occasions. The Troops were very much fatigued, the greater Part of them having been under Arms all Night, and made a March of upwards of Forty Miles before they arrived at Charlestown, from whence they were ferryed over to Boston.

The British could have viewed this style of warfare as an atrocity in and of itself.

Appeals for a New Direction

Fourth, there is direct appeal to God for Justice in the colonies. This is coupled with a determination to be free or die. This is the magnitude of the perceived abuses of the British government on the colonies. Massachusetts was the center of resistance to British actions in the colonies. It was common, especially there, to view the British as attempting to enslave the colonists.

Fifth, like a significant number of colonists, Warren left the door open to reconciliation with Britain. He professes loyalty to King George while accusing his government of abusing the colonies. Warren at once looks to King George to save the colonies and then, more broadly to his audience, the British people, to do so. Finally, he pleads with the people of Great Britain, under Divine Guidance, to save the colonies and Great Britain itself from the ruin they will surely face if the abuses of the British government go unchecked.

Moving Forward

As the American Revolutionary movement gathered momentum, the colonial position would change. We will see the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776, we see appeals to Rights of Englishmen begin to recede as Natural Rights theory makes its imprint. By July 1776, the idea that the King might intervene for the benefit of his American colonies also gives way. Instead, we see in the Declaration of Independence an indictment of the king.

While messages like Joseph Warren’s Letter helped to refine and consolidate the colonial position, they not be the final word. Instead, these sentiments were but a step in the evolution of revolutionary thinking in Colonial America.