The Battle of Lexington and Concord launched the American Revolutionary War on April 19, 1775. The surrender following the Battle of Yorktown ended the land war in North America exactly 6½ years later, on October 19, 1781.

From 1775 until near the end of 1778, the Revolutionary War was fought largely around New York, Boston, and other cities in the Northern colonies. King George III, however, believed that there was Loyalist (pro-British) sympathy in the Southern colonies. In his mind, if only he could arouse those sympathies, the revolution could be put down. British focus shifted to the Southern colonies, particularly Virginia and the Carolinas, in the hopes that the presence of British troops would inspire Loyalist opposition to the Revolution. This southern campaign set the stage for the Battle of Yorktown.

The Southern Campaign

General Charles Cornwallis joined the British Army in 1757. In 1776, with the rank of Lieutenant General, he began his North American military service. In November 1778, Cornwallis returned to England to be with his dying wife. She died in February 1779.

In November 1778, British General Henry Clinton ordered an attack on Savannah, Georgia. The British quickly took Savannah and re-established a royal governor for Georgia. While the British easily overpowered the Continental Army defenders of the city, the attack failed to accomplish its political objectives. Loyalist sentiment was much smaller than believed. Even worse for the British, though, their plundering of plantations on the way to Savannah turned some Loyalists against them and further energized Revolutionary sentiment.

The Carolinas

Cornwallis returned to North America in July 1779, taking command of British forces in the Southern colonies. Following the capture of Georgia, British troops became engaged in a back-and-forth with Continental forces in South Carolina. British Army forces combined with the British Navy to surround and ultimately force the surrender of Charleston in May of 1780. In reoccupying the rest of South Carolina, British forces forced the Continental Army back to North Carolina.

Under famed Continental commanders, such as “the Swamp Fox,” Francis Marion and General Daniel Morgan, Continental Army, and colonial militia forces were able to inflict heavy casualties on British forces, including a savage victory at Kings Mountain, South Carolina, and the Battle of Guilford Court House (now Greensboro, North Carolina) in March of 1781.

Following the Battle of Guilford Court House, Cornwallis withdrew to the North to resupply and lick his wounds. General Nathanael Greene, chosen by Congress as commander of the Southern theater, took the opportunity to drive back into Georgia and South Carolina. After combining with local guerrilla forces already there, he was able to retake much of Georgia and South Carolina, leaving the British in control of Savannah and Charleston.

The Virginia Campaign

General Cornwallis reasoned that he needed to be eliminate Virginia as a resupply source for the Continental Army operating in the Deep South. On December 20, 1780, General Benedict Arnold (once a star of the Continental Army, now a traitor and British General, following his betrayal of the defenses of West Point in September of 1780) took 1,500 troops from New York to Portsmouth, Virginia. From there, he conducted raids against other cities, such as Richmond.

British General William Phillips was sent to connect with Arnold. George Washington, perceiving the threat from Arnold and Phillips in Virginia, sent the Marquis de Lafayette and his force of 3,200 men to defend Virginia. Phillips died on May 13, 1781, likely from typhus or malaria. Cornwallis arrived in Petersburg, Virginia with his troops about a week later and assumed command. British Forces then numbered about 7,200. After Lafayette linked up with additional forces under the command of Baron von Steuben, American forces numbered about 4,500 under Lafayette’s command.

In July, near New York, Washington met with his French allies. Washington advocated an attack on New York, where the British were now outnumbered three-to-one. French General Jean-Baptiste Rochambeau, however, proposed a different course of action. He suggested that the French fleet in the West Indies under Admiral de Grasse could sail to an easier target further south. On August 14, Washington received a letter from de Grasse that he was bound for Virginia with 28 ships and 3,200 men.

Meanwhile, General Cornwallis was ordered to construct a fortified naval base to give shelter to British ships of the line. Cornwallis chose to build near Yorktown, Virginia. The site for the battle was now certain.

The Battle of Yorktown

Buildup

On August 19, a combined force of 4,000 French and 3,000 American soldiers began the march from Rhode Island to Virginia. Washington sent fake dispatches and otherwise engaged in a campaign of deception to conceal the troop movements and their true destination. It was key to keep the British command focused on New York.

On August 30, de Grasse arrived at Yorktown and landed his troops to meet up with Lafayette’s force. On September 5, British ships under Admiral Thomas Graves arrived to resupply and relieve Cornwallis. The following day, de Grasse’s force joined the British fleet in the Battle of Chesapeake, forcing Graves to withdraw on September 10 for repairs in New York.

With the arrival of the troops from Rhode Island, American and allied troop numbers soared to more than 16,000. This was more than double the forces available to Cornwallis. Transports arrived on September 26 with more men and equipment, giving Washington command of 7,800 French soldiers, 3,100 militia, and 8,000 Continental Army soldiers.

Siege and Conquest

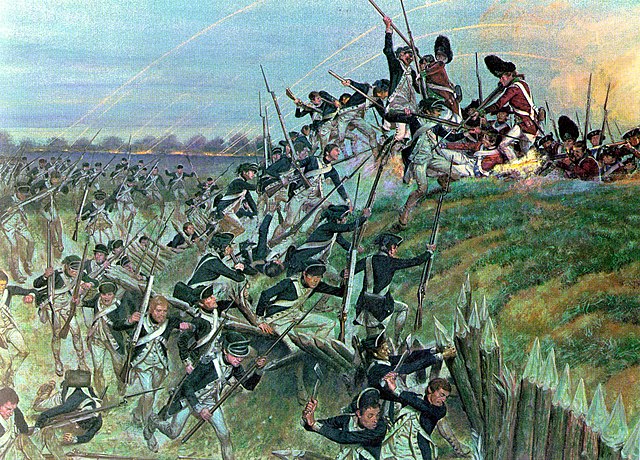

On September 28, Washington laid siege to Yorktown. Washington began an advance toward Yorktown on September 29. Cornwallis withdrew from most of his outer defenses and was anticipating a relief force of 5,000 men. American and French forces occupied the abandoned defenses and established artillery positions there. Over the next two weeks, the two sides exchanged artillery fire, and attempts to take the remaining British outer defenses were repelled.

On October 14, the last two British redoubts finally fell. This allowed Washington to position artillery to fire directly on Yorktown from three sides. British attempts to evacuate were foiled by bad weather. With new artillery arriving to support the American cause and no hope of escape, Cornwallis knew his position was hopeless.

On the morning of October 17, a British officer approached the American lines under a flag of truce. Major Alexander Ross negotiated a surrender with American and French commanders. American and French soldiers occupied British positions that afternoon.

Surrender at Yorktown

The British had requested traditional honors of war for a surrendering force. These included marching out with bayonets fixed and flags flying. Washington, noting the British had denied such courtesies to the Americans at Charleston, refused. The British were to march out with muskets shouldered and flags furled.

General Cornwallis claimed he was ill and refused to attend the surrender. In his place, General O’Hara, his second in command, was sent to offer his sword to General Washington. O’Hara tried to offer his sword to General Rochambeau who motioned to General Washington. Washington refused to accept the sword in surrender and motioned for General Benjamin Lincoln. General Lincoln was Washington’s second in command. He had also been the commander of American forces who was forced to surrender at Charleston. Lincoln had been returned in an earlier prisoner exchange. Lincoln accepted O’Hara’s sword in surrender.

In all, the British surrendered 8,000 men, over 200 artillery pieces, thousands of muskets, numerous transport ships, plus wagons and horses. The surrender ended the land battle in North America. The Revolutionary War, however, was part of the broader Seven Years War, and some hostilities continued.

Negotiations for a lasting peace began in the aftermath of the Battle of Yorktown and Cornwallis’ surrender. A final peace between the United States and Great Britain would be concluded with the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

Articles of Capitulation

The following articles of capitulation were signed on October 19, 1781, in the aftermath of the Battle of Yorktown. George Washington refused to accept Article X below.

Settled between his Excellency General Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the combined Forces of America and France; his Excellency the Count de Rochambeau, Lieutenant-General of the Armies of the King of France, Great Cross of the royal and military Order of St. Louis, commanding the auxiliary Troops of his Most Christian Majesty in America; and his Excellency the Count de Grasse, Lieutenant-General of the Naval Armies of his Most Christian Majesty, Commander of the Order of St. Louis, Commander-in-Chief of the Naval Army of France in the Chesapeake, on the one Part; and the Right Honorable Earl Cornwallis, Lieutenant-General of his Britannic Majesty’s Forces, commanding the Garrisons of York and Gloucester; and Thomas Symonds, Esquire, commanding his Britannic Majesty’s Naval Forces in York River in Virginia, on the other Part.

Source: mountvernon.org

ARTICLE I. The garrisons of York and Gloucester including the officers and seamen of his Britannic Majesty’s ships, as well as other mariners, to surrender themselves prisoners of war to the combined forces of America and France. The land troops to remain prisoners to the United States, the navy to the naval army of his Most Christian Majesty.

Granted.

Article II. The artillery, arms, accoutrements, military chest, and public stores of every denomination, shall be delivered unimpaired to the heads of departments appointed to receive them.

Granted.

Article III. At twelve o’clock this day the two redoubts on the left flank of York to be delivered, the one to a detachment of American infantry, the other to a detachment of French grenadiers.

Granted.

The garrison of York will march out to a place to be appointed in front of the posts, at two o’clock precisely, with shouldered arms, colors cased, and drums beating a British or German march. They are then to ground their arms, and return to their encampments, where they will remain until they are despatched to the places of their destination. Two works on the Gloucester side will be delivered at one o’clock to a detachment of French and American troops appointed to possess them. The garrison will march out at three o’clock in the afternoon; the cavalry with their swords drawn, trumpets sounding, and the infantry in the manner prescribed for the garrison of York. They are likewise to return to their encampments until they can be finally marched off.

Article IV. Officers are to retain their side-arms. Both officers and soldiers to keep their private property of every kind; and no part of their baggage or papers to be at any time subject to search or inspection. The baggage and papers of officers and soldiers taken during the siege to be likewise preserved for them.

Granted.

It is understood that any property obviously belonging to the inhabitants of these States, in the possession of the garrison, shall be subject to be reclaimed.

Article V. The soldiers to be kept in Virginia, Maryland, or Pennsylvania, and as much by regiments as possible, and supplied with the same rations of provisions as are allowed to soldiers in the service of America. A field-officer from each nation, to wit, British, Anspach, and Hessian, and other officers on parole, in the proportion of one to fifty men to be allowed to reside near their respective regiments, to visit them frequently, and be witnesses of their treatment; and that their officers may receive and deliver clothing and other necessaries for them, for which passports are to be granted when applied for.

Granted.

Article VI. The general, staff, and other officers not employed as mentioned in the above articles, and who choose it, to be permitted to go on parole to Europe, to New York, or to any other American maritime posts at present in the possession of the British forces, at their own option; and proper vessels to be granted by the Count de Grasse to carry them under flags of truce to New York within ten days from this date, if possible, and they to reside in a district to be agreed upon hereafter, until they embark. The officers of the civil department of the army and navy to be included in this article. Passports to go by land to be granted to those to whom vessels cannot be furnished.

Granted.

Article VII. Officers to be allowed to keep soldiers as servants, according to the common practice of the service. Servants not soldiers are not to be considered as prisoners, and are to be allowed to attend their masters.

Granted.

Article VIII. The Bonetta sloop-of-war to be equipped, and navigated by its present captain and crew, and left entirely at the disposal of Lord Cornwallis from the hour that the capitulation is signed, to receive an aid-de-camp to carry despatches to Sir Henry Clinton; and such soldiers as he may think proper to send to New York, to be permitted to sail without examination. When his despatches are ready, his Lordship engages on his part, that the ship shall be delivered to the order of the Count de Grasse, if she escapes the dangers of the sea. That she shall not carry off any public stores. Any part of the crew that may be deficient on her return, and the soldiers passengers, to be accounted for on her delivery.

Article IX. The traders are to preserve their property, and to be allowed three months to dispose of or remove them; and those traders are not to be considered as prisoners of war.

The traders will be allowed to dispose of their effects, the allied army having the right of preemption. The traders to be considered as prisoners of war upon parole.

Article X. Natives or inhabitants of different parts of this country, at present in York or Gloucester, are not to be punished on account of having joined the British army.

This article cannot be assented to, being altogether of civil resort.

Article XI. Proper hospitals to be furnished for the sick and wounded. They are to be attended by their own surgeons on parole; and they are to be furnished with medicines and stores from the American hospitals.

The hospital stores now at York and Gloucester shall be delivered for the use of the British sick and wounded. Passports will be granted for procuring them further supplies from New York, as occasion may require; and proper hospitals will be furnished for the reception of the sick and wounded of the two garrisons.

Article XII. Wagons to be furnished to carry the baggage of the officers attending the soldiers, and to surgeons when travelling on account of the sick, attending the hospitals at public expense.

They are to be furnished if possible.

Article XIII. The shipping and boats in the two harbours, with all their stores, guns, tackling, and apparel, shall be delivered up in their present state to an officer of the navy appointed to take possession of them, previously unloading the private property, part of which had been on board for security during the seige.

Granted.

Article XIV. No article of capitulation to be infringed on pretence of reprisals; and if there be any doubtful expressions in it, they are to be interpreted according to the common meaning and acceptation of the words.

Granted.

Done at Yorktown, in Virginia, October 19th, 1781.

Cornwallis,

Thomas Symonds.

Done in the Trenches before Yorktown, in Virginia, October 19th, 1781.

George Washington,

Le Comte de Rochambeau,

Le Comte de Barras,

En mon nom & celui du

Comte de Grasse.