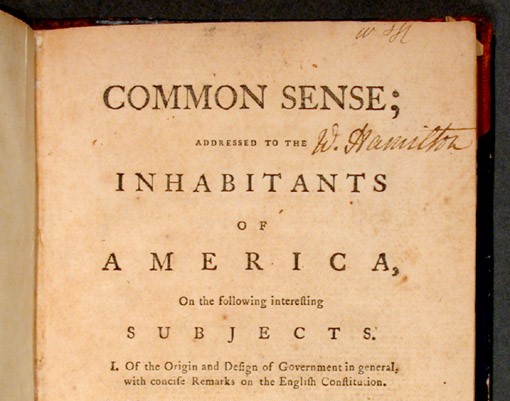

On January 10, 1776, Philadelphia printer Robert Bell published an anonymous pamphlet titled Common Sense. It quickly became the most widely read colonial publication in the American colonies. At the time, there was still much debate about whether the American goal in the war with Britain should be reconciliation or independence. Common Sense argued for independence.

By the end of March, the secret was out, and people knew that Thomas Paine was the author. Also by this time, Paine had allowed the pamphlet to be published by many printers and in many newspapers. By allowing anyone to publish it, Paine made certain that he would not financially benefit from his work.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine was born January 29, 1737 in Thetford, Norfolk, England, to a Quaker father and Anglican mother. He tried various occupations in England, leading to repeated failure. Paine had two short marriages – one ended by the death of his wife in childbirth, and one ending after just a few years in separation.

Paine developed an interest in politics. He grew to believe that common people were unfairly treated in English society. He found that he had the skill to communicate his beliefs and set about doing so. At the time, Paine was working as a tax collector. Benjamin Franklin attended one of his speeches in 1772, in which Paine aired the grievances of local tax collectors. Franklin was representing the colony of Pennsylvania in London. After the speech, Franklin and Paine met, with Franklin suggesting Paine come to America and even to Franklin’s hometown of Philadelphia.

American Revolutionary Writing

On November 30, 1774, Paine arrived in Philadelphia. There, he helped found the Pennsylvania Magazine. He served as the editor for a year and a half and began a more extensive writing career. His well known revolutionary writings include the pamphlet Common Sense (1776) and a series of pamphlets titled The American Crisis (1776-1783). Paine served in the Colonial Army in the Revolutionary War. At the conclusion of the war, however, Paine was once again in dire financial straits.

Involvement in French Revolution and Edmund Burke

In 1787, Paine returned to Europe, originally to promote an engineering project near Philadelphia. His attention quickly turned back to politics. In July of 1789, the French Revolution overthrew the French monarchy. Edmund Burke, a member of the British Parliament who supported letting the American colonies go in the American Revolution, was appalled at what had happened in France. In 1790, Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Paine, in turn, published his Rights of Man in 1791, to answer Burke’s arguments. The two continued the debate with a response from Burke, followed by Paine’s The Rights of Man, Part II in 1792.

Paine was ultimately charged with sedition in England for his writings in 1792. An enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, Paine was elected to the National Convention. In the aftermath of the revolution, various factions saw their power grow and wane. When a faction hostile to Paine gained in power, he was arrested and narrowly escaped execution.

Deism and Return to the United States

In 1794, Paine published the first part of The Age of Reason, a critique of perceived corruption in Christian churches and a challenge to the idea of revealed religion generally. Parts II and II were subsequently published in 1795 and 1807, respectively. In 1802, Paine returned to the United States. Seven years later, he died June 8, 1809, in New York.

Common Sense Historical Context

Colonists and the British Army fought the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April, 1775. This battle kicked off the American Revolution. Though war had begun, there was a division in the colonies on the purpose of the war.

Was the war to get Britain to undo the offensive things she had done and to reconcile? Those seeking reconciliation wanted the war to end and the King to respect colonists’ rights as Englishmen. The sticking point here was that the colonists and the British government were far from seeing eye to eye on what the colonists rights were.

Alternatively, was the war to completely break away from England, to achieve independence? Advocates for this position wanted British government completely out of North America. They sought self-determination and the opportunity to craft a new government uniquely for Americans.

As we shall see, Thomas Paine argued forcefully for independence. In turn, Common Sense helped to sway public opinion in that direction.

Society vs Government

In the opening pages of Common Sense, Paine seeks to lay out some fundamental principles. He invites the readers to consider fundamental questions about the nature and purpose of government.

The first principle we need to understand is a distinction between society and government. In modern terms, we might call this the distinction between the state and civil society. We have written about that some here.

Paine tells us that society and government are distinct in purpose and origin. Society is based upon our wants and has the effect of unifying our “affections” in the community. Society encourages interaction, and acts as a “patron” to its members. In short, society is the system of voluntary social interaction which enables cooperation and collective action. Paine writes that

the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least.

Government, on the other hand is based upon human wickedness. Instead of unifying our affections, its purpose is to “restrain our vices.” Where society encourages interaction, government promotes distinctions. Government serves not as a “patron” of community members, but rather as the “punisher” of wrongdoers. The aim of government is security, and the best government is the one that provides security at the lowest cost. Paine tells us that

Society in every state is a blessing, but government in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one.

Origins of Government

Paine asks us to consider a thought experiment. Imagine that a few settlers go to an uninhabited, isolated corner of the Earth. They are in a state of “natural liberty” and are most interested in society. Each person will need help from the others to survive, so cooperation is in everyone’s interest. Cooperation for such core things as establishing housing and caring for the sick is the natural response. A social structure based upon common interest and voluntary cooperation arises. This is Paine’s “society,” or what we may call civil society today.

Government is unnecessary for this community. As it grows, however, things change. People live further apart because of geographical growth of the community. Interpersonal ties, once sufficient to bind the community together, weaken because of distance. Though ties may be close with those living close together, more distant relationships are weaker.

The community creates a “State House” where all may gather to consider community issues and establish rules or regulations. Enforcement of rules is informal, through general disapproval of rule breakers. As the community continues to grow, community meetings become less practical as there are too many community members. Instead, it becomes practical to send some representatives to consider rules for the community. Enforcement of rules may become more formal, as we see the rise of government in response to the failure of human virtue which was originally sufficient to bind the community.

Frequent elections and having representatives mingled with the community (without forming a professional political class) they represent help to hold some sense of community input. Different parts of the community continue to have an interest in supporting each other. Paine writes that “on this (not the unmeaning name of the king) depends the strength of government, and the happiness of the governed.”

Hereditary Monarchy

Paine explores the notion of monarchical government. While monarchy is a big problem for him, the idea of hereditary monarchy is a bigger one.

Paine observes that male / female is a natural distinction and good / evil a heavenly one. How, though, do we end up with a “race” of kings? Paine notes that Biblical scripture repeatedly warns the Hebrews against having kings.

Government by kings was first introduced into the world by Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry. The Heathens paid divine honors to their deceased kings, and the [C]hristian world hath improved on the plan by doing the same to their living ones.

Paine tells us that origins of kings likely that they were “the principal ruffian of some ruthless gang.” That said, there are three possible ways someone might become a king. Lot is the first, in which the king as leader of a community is randomly selected. If lot is the principal for selecting a king, it would seem to preclude hereditary succession. The second method for someone to become king is by election. This also is a method which is incompatible with hereditary succession. The third way for someone to become king is by usurpation. Usurpation is taking and holding an office, or position of authority, by force or other illegitimate means.

The Conquest of England

William the Conqueror, was a Duke of Normandy, a French province. In 1066, William invaded England and was crowned King in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day of that year. William was unquestionably a usurper.

All English kings since then have traced their line back to William. If he was a usurper, his usurpation taints his line from the beginning. Even if he were somehow a righteous king, though Paine observes that his descendants may not be, and hereditary succession does not

ensure a race of good and wise men . . . would have the seal of divine authority, but as it opens the door to the foolish, the wicked, and the improper, it hath in it the nature of oppression.

The English monarchy, then is fundamentally illegitimate.

A Common Sense Case for Independence

Beyond arguing that the English monarchy is corrupt, Paine notes that war has already begun in America. About the struggle, he writes

The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ‘Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent – of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

The Battle of Lexington was a turning point, before which, even he would have welcomed reconciliation with Britain. The time is past for simply undoing the wrongs perpetrated on the American colonies. Against reconciliation, Paine essentially argues that King George would remain in charge with little reason to believe that the abuses of the past would not return after a cooling off period. He further argues, though, that only an independent continental government keenly vested in local interests can keep the peace.

On the idea of a King in America, Paine writes

I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havock of mankind like the Royal—of Britain.

And, further,

in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.

The American people have the natural right to form their own government. He notes that while colonists often referred to Britain as the mother country, there are colonists from many other countries. America has become and is continuing to become something fundamentally different than Britain.

Are the Colonies Ready for Independence?

Paine notes that some people support reconciliation because they think that the colonies cannot stand on their own. He writes that he has never met anyone on wither side of the Atlantic who did not believe that the colonies would eventually separate from Britain. Whether that is true or not, Paine wants readers to believe that colonial separation is eventually going to happen.

Paine makes several points as to why the colonies are well positioned to separate now.

- Colonial strength in unity, not raw numbers, and unity becomes threatened the larger the colonies grow

- America is rich in resources

- Most “armed and disciplined men of any power under Heaven,” “sufficient to repel the force of all the world.”

- No debt, so financially as strong as possible for prosecuting a War of Independence

- Abundant timber, sufficient to build a navy on the scale of the British Navy, yet that timber will become more distant from the coastline as westward expansion continues

Likewise, there are reasons that Britain is vulnerable

- British Navy must defend far flung territories, so its Navy never concentrated against the colonies

- British Navy has many inoperative ships, so they are weaker than their claimed number of ships would indicate

- British Navy distant, while American Navy would be close

- Britain, as a more mature country, has more commercial interest, and less “patriotism and military defence”

Paine argues, then that America must make an “open and determined declaration for independence.” Such a declaration offers a number of advantages

- It is customary when two nations are at war for an uninterested party to mediate. As long as America sees herself as subject to Britain, that cannot happen and conflict may continue in perpetuity.

- Neither France nor Spain likely to give colonists aid if objective is merely fixing the relationship with Britain.

- As long as we identify ourselves as subjects of Britain, we must be seen as rebels by other nations. It is dangerous for them to support rebels and perhaps breed their own internal rebellions.

- If we write a manifesto and publish it to foreign nations making our case as to the injustice of British rule and assure foreign courts of our peaceful intentions toward them and desire to enter into trade with them we would “produce more good effects on this Continent, than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain.”

Conclusions

Thomas Paine’s writing helped to build and solidify colonial support for independence. His arguments against monarchy, and particularly hereditary monarchy, were compelling to his audience. Likewise, the absurdity of distant British rule of the colonies was widely accepted. Paine made the case for a switch from arguing for the Rights of an Englishman to arguing for the Rights of an American. Since its publication in 1776, Common Sense has remained in print to this day.