Boston, a vital port city within the Massachusetts Bay, stood as a testament to colonial ambition and burgeoning self-governance. It was one of the three major colonial cities, with New York and Philadelphia. The Boston Massacre in 1770 helped fuel the flames of resistance and, ultimately, revolution.

The aftermath of the French and Indian War brought a shift in the colonial relationship with Great Britain. The Crown sought to recoup its war expenses. Parliament implemented a series of taxation measures that ignited a firestorm of resentment amongst the colonists.

The Townshend Acts of 1768, levying duties on essential goods like glass, paper, and tea, were particularly offensive. The Massachusetts House of Representatives petitioned for the repeal of these economic burdens. They issued the Massachusetts Circular Letter, calling for unified colonial resistance. This further strained the already tense relationship with the mother country.

Before the Massacre: Boston Tensions Rise

The British response to this growing colonial defiance was to assert its authority more forcefully. Colonial Secretary Lord Hillsborough’s demanded the dissolution of resistance organizations and the retraction of the Circular Letter. This demand only deepened the divide.

Adding to the volatile atmosphere was an increased military presence in Boston. The arrival of the HMS Romney in 1768 sparked outrage and unrest among the populace. The seizure of John Hancock’s ship, the Liberty, on dubious smuggling charges, further fueled colonial discontent.

The deployment of four regiments of British troops to enforce the unpopular Townshend Acts transformed Boston into an occupied city. This occupation created a constant source of friction between the soldiers and the citizenry. Many Bostonians viewed the presence of a standing army in their midst as a direct threat to their liberty. The withdrawal of two regiments in 1769 did not pacify Bostonians.

On February 22, 1770, the tensions escalated to bloodshed. On that fateful day, an eleven-year-old boy, Christopher Seider, was killed by a customs employee. At the time, he was protesting in front a shop owned by a colonist loyal to the Crown. Boston was now a powder keg, waiting to explode.

The Boston Massacre

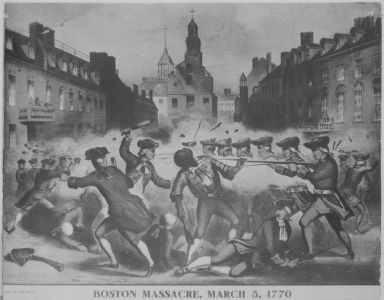

Simmering tensions boiled over into what we know as the Boston Massacre on the evening of March 5th, 1770. Events unfolded outside the Customs House on King Street, a building that symbolized the very taxation policies that irritated the colonists. Private Hugh White, a lone British sentry, found himself confronted by a growing crowd.

The initial confrontation involved Edward Garrick, a local wigmaker’s apprentice. Garrick walked by the office, yelling that an officer inside had not paid for his wig. White reprimanded him for his conduct. The situation quickly escalated, culminating in White striking the young man with his musket. This drew the attention of more Bostonians, their anger fueled by years of perceived injustices.

As the mob intensified, White called for reinforcements. Captain Thomas Preston, of the 19th Regiment of Foote, and seven additional soldiers arrived. Their presence only further inflaming the already volatile situation. Surrounded and facing a barrage of insults and projectiles, the soldiers grew increasingly apprehensive.

Amidst the chaos, Private Montgomery was struck and fell. He impulsively discharged his weapon and exclaimed, “Damn you, fire!” Montgomery’s actions triggered a deadly volley from the other soldiers, resulting in the tragic deaths and injuries of several civilians. While Captain Preston never ordered his soldiers to fire, the outcome was undeniable: blood had been spilled on the streets of Boston.

The volley resulted in eleven casualties: three immediate deaths, including Crispus Attucks, and two fatally wounded. Six others sustained injuries. Preston ordered his men to cease fire and secured the Customs House with additional troops. Governor Thomas Hutchinson arrived and quelled the immediate unrest by promising a local trial for the soldiers.

Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks was the first martyr of the growing colonial revolutionary movement. Little is known for sure about him. Born in Framingham, Massachusetts, Attucks worked as a sailor. His last name is of American Indian origin, meaning “deer.” Attucks was of mixed African and American Indian heritage. We believe he was a former slave, in part because slave owners often assigned ancient Roman names (like Crispus) to their slaves.

On the day of his death, Attucks was with a group of armed sailors. Brandishing clubs, they marched toward King Street as part of the gathering of colonists around the customs office. When the initial volley from Preston’s soldiers rang out, Attucks was struck in the chest with two musketballs. Because they had no family in Boston, the bodies of Crispus Attucks and fellow sailor James Caldwell were laid in state at Faneuil Hall before their ultimate burials.

Fueling the Flames of Revolution

The immediate aftermath of the Boston Massacre included the arrest of Captain Preston and his soldiers, with the promise of a local trial intended to appease the outraged populace. British troops were withdrawn from the city to Castle Island, a move aimed at de-escalating the immediate crisis.

Despite these attempts to calm the situation, the incident was quickly seized upon by colonial leaders as powerful propaganda. Paul Revere’s now-iconic engraving, though not entirely accurate, depicted a scene of British brutality against unarmed civilians, effectively galvanizing anti-British sentiment across the colonies. The public funerals held for the victims became powerful demonstrations of colonial solidarity and mourning, solidifying the narrative of British oppression.

The subsequent trials of the British soldiers were a significant moment in the unfolding drama. John Adams’ courageous decision to defend the accused, despite his own Patriot leanings, underscored the colonists’ commitment to the rule of law and their desire to demonstrate fairness.

Six of the soldiers were ultimately acquitted on the grounds of self-defense. The conviction of two others for manslaughter, albeit with a symbolic punishment, served as a partial vindication for the colonists.

The Boston Massacre, annually commemorated in Boston, became a potent symbol of British tyranny and a rallying cry for the burgeoning revolutionary movement. This tragic event, coupled with ongoing grievances, propelled the Massachusetts colonists, and indeed the other colonies, further down the path toward independence. The massacre helped set the stage for the armed conflict that would erupt at Lexington and Concord just a few short years later. The “Incident on King Street,” as it was sometimes referred to in Britain, stood as a stark reminder of the escalating tensions and the human cost of the growing divide between the colonies and their mother country.