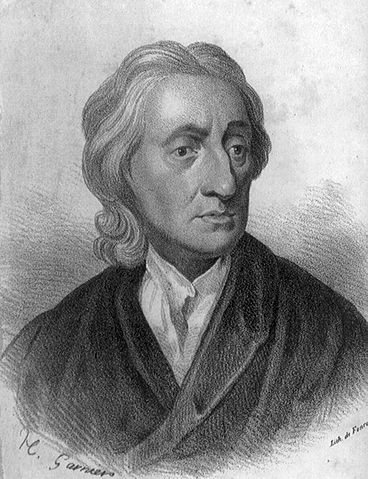

Liberalism was the driving ideology of the American Revolution. It, however, predates the American Revolution by a century. Liberalism can trace its origins to the writings of physician and political philosopher John Locke. His Second Treatise on Government outlines the key elements of liberalism, though the name would come later. Written in about 1679-1680, the work was published in 1689, following the Glorious Revolution in Britain in 1688.

Social Contract Theory

There are two central concepts to Locke’s philosophy: social contract theory and natural law. Social contract theory is not new to John Locke. In fact, in 1651, Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan outlining a different form of social contract. Both Locke and Hobbes explore the idea of a social contract by considering a “state of nature.” Contrasting their theories should help to explain Locke’s.

An Earlier Social Contract Theory

Hobbes’ view of the state of nature, where life is famously described as “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short,” is notably pessimistic. Hobbes’ theory of social contract suggests that to escape this profoundly unpleasant state of nature, people enter into a “contract,” giving all authority to an all-powerful government (the Leviathan) in exchange for protection from the harshness of the state of nature. While the purpose of creating the Leviathan is to escape the problems of the state of nature, the Leviathan is under no obligation to do anything in particular for the people or any person; yet the people are obliged to obey Leviathan.

Locke’s Social Contract

Locke’s theoretical state of nature is much less harsh than Hobbes. Since it is less harsh, the social contract that Locke envisions is less harsh. For Locke, the main problems of the state of nature center around abuses of the natural rights of one person by another. Ultimately, violations of natural law in the state of nature create a state of war between the perpetrator and the victim. This is not a good situation, and everyone is left to judge and punish offenses against themselves.

What is needed is not an all-powerful government, but rather a government to mediate disputes and protect the natural rights of people against abuses by another. Locke’s social contract imposes requirements on the government to uphold the natural rights of people. Ultimately, if the government fails to do so, the people may dissolve the social contract and replace the government. The government is the creation of the people. Locke does not necessarily believe that the first governments arose in this way; the state of nature provides a touchstone to explain the proper relationship between government and governed.

Locke’s philosophy provides a justification for revolution when the social contract is broken. While this right of revolution is not to be trivially exercised, it exists as a last resort for a tyrannical government. This theory of revolution was used to justify the American Revolution, alleging that the King had broken the social contract and ignored pleas to restore it. The Declaration of Independence is a thoroughly Lockean document.

Natural Law

Natural Law is a concept suggesting that laws, or codes of conduct, are inherent in human nature. Rights that are based upon natural law. What is a “right,” though? At its most basic, a right is a check or limitation on what someone may do to another. If we say that someone has a right to free speech, this means that no one may stop another from speaking his views or opinions.

For Locke, there were three fundamental natural rights. These are the rights to Life, Liberty, and Property. (Property was notably changed to the Pursuit of Happiness in the Declaration of Independence.) Since these rights are for everyone, they are necessarily limited. One person’s right may not be exercised in a way that violates someone else’s rights.

Economic Liberalism

In 1776, Scottish law professor, ethicist, and economist Adam Smith published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, generally referred to simply as The Wealth of Nations. This is arguably the first comprehensive work on economics. One of its key features is outlining the operation of a market economy and explaining how that economy works to promote the well-being of members of the community.

Smith’s Wealth of Nations dovetails well with Locke’s philosophy and became the basis for “classical economics.” Because a market economy is based on both property and liberty rights, it is distinctively liberal. For this reason, we view John Locke and Adam Smith as twin sources of liberalism.

Liberalism Today

Other ideologies, such as utilitarianism, have co-opted the word “liberalism” and applied it to some very un-liberal belief structures. Classical liberals today are most likely to be found using labels like libertarianism. The label “liberal” is almost universally misapplied in today’s American context. Let’s explore how other things came to get a false liberal label.

Utilitarianism

Shortly after the American Revolution, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham published An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. A student of Bentham’s, Scottish philosopher James Mill, and his son, John Stuart Mill, further worked with Bentham’s ideas. The school of thought they developed became known as utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism sets aside all notions of rights or natural law. Instead, utilitarianism is based on the idea that there are two major motivations for human behavior: pleasure and pain. Utilitarian ethics is based upon maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. It is a hedonistic philosophy – one that prioritizes pleasure as an ethical principle. The utilitarian goal is often expressed in terms of maximizing utility, rather than using the term pleasure.

Utilitarian Morality

A human action can be evaluated by determining how much utility the action produces. A util is a unit of utility. The morally correct choice is the one that produces the most utility. This presents multiple problems right away.

One problem is how to know how much utility (how many utils) any course of action may produce. If we can’t determine that, it makes selecting the moral choice difficult. For our discussion here, however, we will set aside this issue and assume that you can determine the amount of utility for different choices.

Another problem is whether or not you can know in advance if an action is moral or not. What if you think the net utility of a certain act is 25 utils, yet it turns out to be -10 utils. Is the moral choice based on the person’s evaluation before taking the action or on the actual utility of the action? This is a question on which utilitarians may differ.

Utilitarian Public Policy

This same ethical calculus can be applied to government policy and social organization. Whatever problems it has for individual ethical choices are undoubtedly compounded when this method is applied to large societal questions.

Utilitarians tended to find that many liberal policy positions generated high levels of utility. In particular, John Stuart Mill, in his essay On Liberty, presents a forceful defense of freedom of speech. His defense, though, is based upon the utility of free speech, not a sense of rights or natural law.

Utilitarian justifications for traditionally liberal policy positions gradually began to supplant the original natural law and social contract bases for those policies. Utilitarianism and liberalism, however, are fundamentally contradictory ideologies even if they come to some of the same policy positions. If a natural reciprocal liberty is preeminent as in liberalism, that liberty may produce negative utilitarian outcomes. If utility is primary, policies such as wealth redistribution which would violate liberal rights of liberty and property may become morally required, depending upon the utility calculations.

An initial similarity of many policy positions gradually led to utilitarianism’s subversion of liberalism. This was not the end of the story, however.

John Rawls’ Social Justice Liberalism

In 1971, Harvard Professor John Rawls published his book, A Theory of Justice. In 1993, he published a follow up titled Political Liberalism, in part to answer criticisms expressed by fellow Harvard professor Robert Nozick, a libertarian and author of the 1973 book Anarchy, State, and Utopia, which was a direct response to A Theory of Justice. Rawls attempted to recreate liberalism on a different foundation and in a way that would justify broad government regulation of the economy and an expansive welfare state. These policies were trading under the label liberal at the time Rawls was writing.

State of Nature to Original Position

Rawls abandoned the state of nature justification for the existence of government. Instead, he proposed a thought experiment. What if before we met together to determine how we would organize society? When we have that meeting, we have the inclinations, desires, and intellectual faculties that we do now. To eliminate bias in our consideration, consider that we are not living in society, but instead in the original position, we do not even know what our place in society will be.

Rawls does not suggest that the Original Position ever existed. Instead, it is a tool to help us find what a just society would look like. In the Original Position, how would we define a just society and organize social arrangements, knowing that we would have to live in the society we arrange.

Principles of Justices

From the Original Position, Rawls suggests that justice will be defined by two principles. The first principle is the greatest equal liberty principle. This principle states that each person in society has an equal right to a maximum set of basic liberties compatible with all having the same liberties. On its own, this could be compatible with Locke’s natural rights which also are necessarily limited by the requirement that everyone have the same set of rights.

The second principle of justice is the maximin principle and has two parts. The first part, the difference principle, says that socioeconomic inequalities are permissable only if they benefit the least advantaged in the community. The second part, the equal opportunity principle, requires that inequalities must be attached to “offices” (positions in society) that are fairly open to all with a fair equality of opportunity.

These principles are ranked. Most important is the greatest equal liberty principle, followed by the equal opportunity principle, then the difference principle.

Liberalism is grounded in equal rights and government protection of those rights. Rawlsian justice, however, brings in a notion of equality of outcomes. This type of egalitarianism is at odds with natural law and natural rights.

Rawls’ philosophy is intricate and certainly covers more than we have covered here. We could write a whole series of articles on his work, yet we believe we have fairly shown how he has influenced thought that flies under the liberal flag.

Final Thoughts

So, when you say someone is liberal, are they really? Knowing what different philosophical positions really are is important to having useful discourse. This has, necessarily, been a quick overview of liberalism and how the label has come to be applied to other ideas.

Whether you are a liberal, a utilitarian, an advocate of Rawlsian justice, or believe in something completely different, make an effort to be reflective on both your position and the positions of others you talk to. Self-reflection and taking the time to know what someone else is really talking about can allow us to communicate better and maybe be able to persuade others.