Today, many people claim that the United States was “founded on slavery.” America’s history contradicts that claim. American slavery certainly existed leading up to the founding period. It existed in much of the country in the early American Republic. It is simply untrue, though, that the United States was, in any meaningful sense, “founded on slavery.” Some people endorsed slavery, but it was generally an awkward match for the colonies as a whole. Indeed, slavery was a majorly divisive issue since its introduction to the colonies.

Caveats

Slavery Universal in World History

As we begin a discussion of American slavery, there are some things it is important to keep in mind. First is that slavery has been a feature of every civilization in the world. It is not unique to the West. That does not justify slavery. It does illustrate that slavery is not a “stain on American history” or even a “stain on Western history.” Slavery is simply a stain on human history. There is no major human civilization in the history of the world that has not practiced slavery.

Slavery still exists throughout much of the world today. It is not just illegal slavery that still exists. Today’s slavery takes many forms including private sector forced labor, state forced labor, and forced sexual exploitation. Estimates are that as many as 40 million people, from all races, are enslaved around the world today. Some of that slavery is legal. Some of it is not.

Illegal slavery exists as a law enforcement concern in countries that have outlawed slavery. Some countries that have recently outlawed slavery have done little to enforce the ban. Legal slavery, however, still flourishes in many countries. In 2020, the World Economic Forum reported that “slavery is not a crime in almost half the countries in the world.” Indeed, as of 2020, 94 countries had no criminal law prohibiting slavery.

American Colonies No Exception

Finally, we should be clear about the context of this article. We will show that characterizing slavery as foundational to the American founding or early American political history is incorrect. We do not, however, deny what is plainly true. Slavery existed and had support from significant proportions of the American population, most concentrated in the South. We do not dismiss the brutality of the institution or minimize the impact on those subjected to it. Slavery is and always has been an abhorrent institution.

Instead of being foundational, from the beginning – and even before the beginning – of the country, many people sought to end slavery. They recognized that slavery did not fit with the ideals of the American Revolution. In response to that realization, they wrestled with how to get rid of slavery. Not only did they recognize the problem, after the colonies declared independence, many states acted to end slavery. Interestingly, a number of critics of slavery were themselves slaveholders who recognized the institution must go.

Seventeenth Century Foundations of British American Slavery

To begin, we must first look at slavery’s arrival in the British North American colonies. This tragic story begins in 1619.

Late August 1619 – São João Bautista’s Ill-Fated Journey

In August 1619, the São João Bautista was sailing from modern-day Angola to Veracruz in modern-day Mexico. Scores of captured Africans on board were on their way to being sold into slavery. Portuguese slavers likely captured or bought the transported Africans as part of their wars against the Kingdom of Ndong. Victorious African tribes often sold prisoners of war into slavery. Then, slave traders would ship them to Portuguese or Spanish colonies in the Americas.

At this time, England had the colony of Virginia in North America. England wanted to expand its colonial interests in the Americas. The crown sought to slow further Spanish and Portuguese expansion on the continent. England used privateers to intercept Spanish and Portuguese ships. A privateer ship is a privately owned ship that a government has commissioned to act on behalf of a government. Countries issue a special commission (often called a letter of marque) to seize ships or contraband. The White Lion and the Treasurer were two such privateer ships.

In August 1619, the White Lion and Treasurer intercepted the São João Bautista. Many of the intended slaves had already perished on the journey. The crews divided the remaining captives between the White Lion and Treasurer. The White Lion was sailing under a Dutch flag. She arrived at Port Comfort (now part of the city of Hampton) in Virginia. The White Lion brought about twenty African captives. Upon arrival, the captives were purchased in exchange for food, according to a letter by John Rolfe back to the Virginia Company of London.

Existing Slavery in North America

Some Indian tribes practiced slavery. Portuguese and Spanish colonists brought the institution of slavery with them to their colonies. Slavery was nothing new in the Americas. Slavery existed throughout the world for centuries before, but this was the beginning of the story of slavery in British North America.

Virginia law did not provide for chattel slavery (the ownership and trading of other human beings as property). Instead, these people would legally have been indentured servants. The distinction is significant in theory but can break down in practice. A slave is the property of another person. An indentured servant is required to work for someone for a fixed period of time.

Slavery Versus Indentured Servitude

Someone who wanted to travel to the Americas might not be able to afford it. To make the journey, the immigrant might find a sponsor in America. The sponsor pays for passage. The immigrant pledges himself to work for the sponsor for a specific term, perhaps seven years. This period of labor pays off the debt. The agreement specifying the length and terms of the work commitment is an indenture. The original sponsor might be able to transfer the indenture to someone else. At the end of the period of indenture, the person is free to get on with his or her life. People commonly came to North America under indentures. This was one way to alleviate pervasive labor shortages in the European colonies.

Indentured servitude could break down into slavery. This happened if the period of indenture became lifetime. Often (but not always) this happened with captured Africans brought to the British colonies. Legitimate indentured servitude is a voluntary relationship. It does not describe the experience of most Africans brought to the Americas in this time.

Slavery Laws to be Written

It would take time for the British colonies to get their laws caught up to the idea of slavery. In Virginia, this would take until 1661. Until then, there was often a corrupted form of indentured servitude without any end to the period of indenture. As a practical matter, this corrupted form of indentured servitude was slavery.

March 8, 1655 – Johnson v Parker

From Indentured Servant to Master

Some Africans did complete a period of servitude and earned their freedom. One such person is Antonio. Like the 1619 captives, slave traders had captured Antonio in modern-day Angola. The traders sold him as an indentured servant to a Virginia farmer.

Antonio survived an attempt by the Powhatten tribe to evict the English from the Tidewater region of Virginia in 1622. In 1623, a woman named Mary moved to the settlement. She and Antonio married. Somewhere between 1635 and 1647, Antonio completed the terms of his indenture and was freed from service. Antonio changed his name to Anthony Johnson. After he was freed from his indenture, he started his own farm and acquired five indentured servants.

John Casor

One of these indentured servants was John Casor. Johnson went to court, claiming that his neighbor Robert Parker was unlawfully depriving him of Casor’s labor. Parker was allegedly doing this by enticing Casor to leave Johnson and telling him that he was a free man.

Casor claimed that he came to Virginia under terms of a seven or eight year indenture. He also claimed that Anthony Johnson had knowingly held him longer than the term of his indenture. Johnson claimed that he had never seen an indenture for Casor, but instead held him for life.

Judicial Acknowledgment of Slavery

Johnson won the case. The court ordered that Johnson could claim Casor and that Parker had to pay Johnson damages. The court ruled that Casor was permanently bound to Johnson. Without slavery directly mentioned in the court’s order, the court effectively recognized that Casor was the slave of Johnson. Original documents are available here.

This court recognized for the first time in British America the alleged right of one person to enslave another. In an irony of monumental and tragic proportions, this ruling was the result of one Black man suing to enslave another Black man.

1688 – Germantown Friends’ Protest Against Slavery

Throughout the 1660s and 1670s, the colonies gradually adopted laws to recognize and regulate slavery. The states were establishing slavery’s legal status, but opposition to the institution was also developing. One of the earliest moral protests against slavery was a Quaker petition in Germantown, Pennsylvania. This was likely the first indictment of slavery by a religious body in the Western world.

Who are the Quakers?

The religious sect known as the Quakers was very young in 1688. Quakers were one of the dissenting groups to appear in England in the wake of the English Civil War (1642-1651). One of the disaffected men was George Fox. He taught that people can have a personal experience with Jesus Christ, without the need of clergy.

In his autobiography, Fox reported that members of his group were first called Quakers after he appeared before magistrates on a charge of blasphemy. He told the magistrates that they should tremble at the word of God, an apparent reference to Isaiah 66:2. The formal name for the Quakers is the Society of Friends.

Some Quakers traveled to the New World. Many Quakers settled in Pennsylvania after Puritan persecution forced them out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1861, a Quaker, William Penn, founded Pennsylvania. Quaker principles, including a broad freedom of religion, generally governed Pennsylvania.

The Germantown Meeting

A meeting of the Quaker group in Germantown in 1688 resulted in the drafting of a powerful indictment of slavery. Let’s take a look at the arguments in the petition. The original document is available here.

The petition begins by stating opposition to trafficking in people. It then asks the question, who would accept being treated in this way? Who would willingly be made a slave for life? They note that seafarers are afraid of strange vessels, concerned they might be Turkish. (At the time, there was a real threat of being captured on the high seas and sold into slavery in Turkey.) How, though, is European slavery better than Turkish slavery?

Uncharacteristically for the time, the petition says that enslavement of Negroes is not any better than enslavement of white people. Further, they argue it is even worse for Christians to engage in slavery than the Turks. Not only are the Africans enslaved, they are often stolen. further compounding the sin of the slave trade.

The Golden Rule

Matthew 7:12 (KJV) states “whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.” The petition doesn’t directly make the scriptural reference. It does, though, assert its moral principle, that we should treat people like we want them to be treat us. This is the moral foundation of the petition’s indictment of slavery. Implicitly, then, the authors of the petition recognize the humanity of the Africans.

If we would not accept being slaves, we should not enslave others. The petition does not stop there, however. It was common in slavery for slave sales to split up slave families. Who would agree to having your husband or wife separated from you and sold to someone else? Who would agree to having his or her children separated from them and sold to someone else? What would be worse than having someone rip our families away from us? If we cannot accept someone doing that to us, we must not do it to others.

Is Christianity Compatible with Slavery?

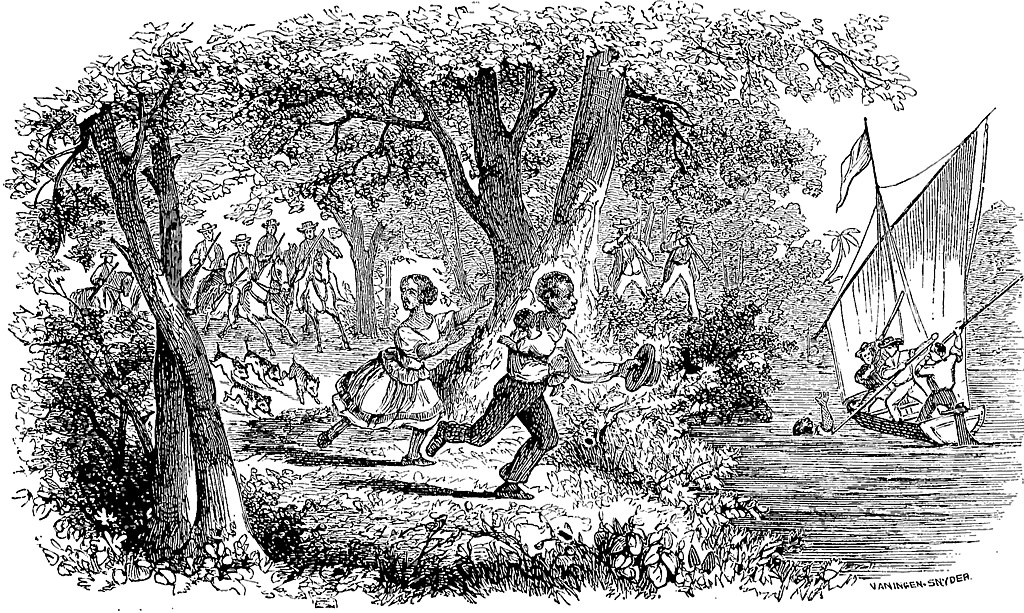

Slavery, then, is certainly unfit for a Quaker. The petition boldly proclaims that slaves should be freed not only in the North American colonies, but also throughout Europe. What if the slaves should join together and fight for their freedom? What if they tried to treat their former masters like their masters had treated them? Could we really blame them for doing so? In fact, would not the “Negroes” have as strong a right to fight for their freedom as the slaveholders claim they have to hold them?

The petition closes by asking that the higher Quaker authorities consider the matter. They ask those who might believe slavery is a good thing to inform them how it might be that Christians have the liberty to engage in slavery. Clearly, this is a challenge that they believe cannot be met.

Demise of the Petition

Local Quakers prepared the petition at a meeting in Germantown. They then sent it for consideration to a Monthly Meeting in Dublin, Pennsylvania, a couple of months later. At this meeting, the Dublin Quakers determined that the topic was too weighty to address there. They referred the matter to an Annual Meeting in Burlington, Pennsylvania. Ultimately, the Quakers at the Annual Meeting did not address the Germantown petition. Again, it was considered too major a topic to handle.

While this petition did not immediately lead to change, it shows the existence of opposition to slavery from its beginning in British North America. Some of the same sentiments expressed here would cause George Washington to begin to turn away from slavery. This petition would also come to help inspire the growing abolition movement of the 1830s.

Slavery and American Independence

April 14, 1775 – Pennsylvania Abolition Society

Quaker activists and members of some other religious organizations formed The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage in Philadelphia on April 14, 1775. The group was reorganized in 1784 following loss of many of its members and then incorporated in 1789. The organization still exists today, devoted to fighting discrimination and racism and promoting multiculturalism.

The origins of the group are in the anti-slavery activities of Philadelphia Quakers. Other religious organizations had joined Quaker activists in petitioning the state legislature to end the importation of slaves. These efforts resulted only in maintaining a tax on importing slaves, thus discouraging the importation of slaves into Pennsylvania.

Activism through the Courts

The group can trace its origins to a 1773 case of a Virginia man, Benjamin Bannarman. He had purchased an Indian woman, Dinah Nevil, and her four children from a New Jersey man, Nathaniel Lowry. Lowry was to deliver the slaves in Philadelphia. Nevil publicly protested that she and her children were free. A group of Quaker citizens, led by Israel Pemberton, filed suit on her behalf. For two years, Quaker activists focused on this case.

After losing in court, activists formed the new Society and met sporadically in 1775. About two-thirds of the founding members of the Society were Quakers. They continued to seek legal ways to free Dinah Nevil. They also were active in protecting free Blacks.

April 19, 1775 – Battle of Lexington and Concord

In April 1775, the British Army launched a plan to confiscate colonial weapons stored in Concord, Massachusetts. A force of about 700 British troops set out from Boston to march to Concord. Early in the morning of April 19, four days after the Society was formed, British and colonial forces met on a field in Lexington. As the sun was rising, someone fired a fateful shot on that field in Lexington. We don’t know who fired that shot. The British forces quickly cleared the battlefield of opposition.

The British continued on to Concord. An alarm went out to militias in the area, including in other colonies. As the British returned from Concord to Boston, colonial forces harassed them, inflicting a number of casualties. The Revolutionary War had begun.

Quaker Neutrality

In the midst of the new war, Quakers adopted a stance of neutrality. They did not take sides between the British colonizers and the American colonists. This was part of an effort to promote peace. It also led them to withdraw from public affairs.

The Quaker neutrality spelled trouble for the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. First, the community viewed Quakers with some suspicion because of their neutral stance on the war. Second, the tendency for Quakers to withdraw from public affairs led them to drift away from all forms of activism, including efforts to eliminate slavery and the slave trade. The loss of membership in the Society caused it to languish until 1784, when the Society had to be reorganized.

July 4, 1776 – Declaration of Independence

With the Revolutionary War well underway, calls for independence from Britain were growing. In 1776, the Continental Congress, representing the colonies, agreed to consider a Declaration of Independence. The Continental Congress selected a committee to draft the document. Most prominent on that committee was Thomas Jefferson, from Virginia. Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration. The Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776.

Jefferson’s Rights of British America

In 1774, Jefferson wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America. In it, he covered some of the same themes covered in the Declaration of Independence. About slavery, he wrote the following

The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa; yet our repeated attempts to effect this by prohibitions, and by imposing duties which might amount to a prohibition, have been hitherto defeated by his majesty’s negative: Thus preferring the immediate advantages of a few African corsairs to the lasting interests of the American states, and to the rights of human nature, deeply wounded by this infamous practice.

For Jefferson, abolishing slavery was the end goal. The first step in reaching that goal, as he says here is the abolition of the slave trade. Jefferson was himself a slave owner, so this may seem an unusual or insincere thing for him to say. We don’t have the space to delve fully into Jefferson’s thoughts on slavery here. Suffice it to say that Jefferson looked forward to the eventual end of slavery. He believed that as immigration caught up to the demand for labor, slavery would wither away.

When Jefferson was writing in 1774, ending the slave trade was an important goal in the colonies. Calling it “the great object of desire in those colonies” suggests a broad interest in eliminating slavery.

Slavery in the First Draft of the Declaration

The document signed on July 4, 1776, did not address slavery. Jefferson’s first draft of the document did, however. Let’s consider what the original draft of the Declaration said. Then, we need to know why the Continental Congress removed the portion about slavery.

Most of the Declaration of Independence is a list of grievances against the King of England. Jefferson provided a list of things George III has done that were considered to be horribly offensive. They were so offensive that they justified the North American colonies rebelling against England. In the draft, that list included the following.

he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

Notice what the complaints against the King are here.

- By capturing slaves and shipping them overseas, the king has “waged cruel war against human nature”

- The king sought to keep the slave trade going

- The king has blocked all legislative action to “prohibit or restrain” the unseemly commerce in human flesh

Amendments to the Declaration

The original draft of the Declaration of Independence contained a strong condemnation of the slave trade. It also included and a more implicit condemnation of slavery itself. Why did Congress remove this from the final version? About the change to the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote the following in his autobiography.

The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.

Georgia and South Carolina wanted to continue the slave trade. Some people in the North, even though the North had comparatively few slaves, had been involved in the slave trade. Such an indictment might have been troublesome to them as well.

The most important goal for the Declaration of Independence was unity among all of the colonies. Anything that threatened that could endanger the entire revolutionary process. While there was significant sentiment for at least ending the slave trade, it was not unanimous. Accomplishing that goal would have to be deferred.

Need for Unity Overshadowed Immediate Action on Slavery

Someone might argue that the anti-slavery language should have stayed in the Declaration of Independence. Perhaps, they could have let Georgia and South Carolina go their own way. As a result, Georgia and South Carolina might have reconciled with England. Alternatively, they could have been independent states in North America. The slave trade was not going to immediately end in South Carolina and Georgia either way. The Declaration of Independence wouldn’t change that. Unity for the war effort had to take precedence over condemnations of slavery that would have accomplished nothing.

Slavery was a divisive issue at the very birth of the nation in 1776. To say that the nation was founded on slavery is to suggest that slavery was a founding principle. That would suggest that slavery united those in the cause of forming a new country. The revolutionary movement never united around preserving the institution of slavery. What immediately followed the Declaration makes it very clear that slavery was not a foundational principle of the new country.

Independent States Move to Abolish Slavery

After the Declaration of Independence, the former colonies regarded themselves as equal and autonomous states. At this time, there was little, if any, sense of an American nation. Loyalty was to the new states, and power rested with them. There was no “national” institution with the power to do anything about slavery – or much of anything else, for that matter. If anyone was going to do anything about slavery, the states would do it.

1777 – Vermont Abolishes Slavery

The area now known as Vermont was under the jurisdiction of New York due to a royal decree in 1764. On January 5, 1777, the area declared its independence from New York and called itself the Republic of New Connecticut. In June, they changed their name to Republic of Vermont. By July, a new constitution for Vermont was complete. That constitution was adopted on July 8 and included the following abolition of slavery.

That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent, and unalienable rights, amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty; acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. Therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave, or apprentice, after he arrives to the age of twenty-one years; nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years, unless they are bound by their own consent, after they arrive to such age, or bound by law for the payment of debts, damages, fines, costs, or the like.

With this constitution, Vermont became the first jurisdiction in the West to abolish slavery.

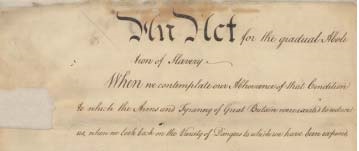

1780 – Pennsylvania Passes Gradual Abolition Act

On March 1, 1780, Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.

This law had several key points. Section I acknowledges all people as the handiwork of God and deserving of equal recognition and protection.

It is not for us to enquire why, in the creation of mankind, the inhabitants of the several parts of the earth were distinguished by a difference in feature or complexion. It is sufficient to know that all are the work of an Almighty Hand. We find in the distribution of the human species, that the most fertile as well as the most barren parts of the earth are inhabited by men of complexions different from ours, and from each other; from whence we may reasonably, as well as religiously, infer, that He who placed them in their various situations, hath extended equally his care and protection to all, and that it becometh not us to counteract his mercies.

- Section 2 recognizes the harm done to those enslaved up to this point. In particular, it recognizes the injustice of separating families through the sale of slaves.

- Section 3 declares that everyone born in Pennsylvania after the act is passed shall be free. The act abolished all hereditary slavery.

- Section 4 provided that children who would have been born slaves shall be servants to those who would have been their owners. This period of servitude was to end at age 28, Conditions of that servitude are to be the same as for an indentured servant with a four year indenture.

- Section 5 required the registration of all slaves and slave owners in the state.

- Section 7 provides that crimes and offenses of Negro and Mulatto people, whether slave or free, shall be handled in the same manner as for any other inhabitant of the state

- Section 13 provides that indentured servitude cannot be for a period longer than 7 years. This prevents unreasonably long indenture periods being used to get around a ban on slavery.

Gradual Abolition of Slavery

Gradual abolition similar to that enacted in Pennsylvania was the most common form of moving to eliminate slavery. While we will note that these acts abolished slavery when they were passed, it was not immediate for all slaves. Laws in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s often accelerated emancipation. These acts generally immediately ended the practice of hereditary slavery. They also, generally, would transform slave status into indentured servant status with a definite endpoint.

Why pursue this gradual approach? While these states moved to eliminate slavery, the sentiment was not unanimous. A gradual approach provided an opportunity to peacefully transition from enslaved labor to free labor. It is easy to look back and declare that abolition should have been immediate and complete. The sentiment is understandable. Such a view is somewhat naive, however, from a practical view.

Immediate and total abolition would have been morally preferable in an ideal world. It almost certainly would have stiffened resistance to abolition and endangered the project. Those advocating a gradual emancipation approach had other objections as well.

Abolition Viewed as Process Not a Single Step

Some abolitionists argued that part of the sin of slavery was creating dependency of the slave upon the master. This dependency damaged the slave’s capacity for self-government. A total and immediate emancipation could severely stress some communities because of this supposed lack of capacity for self-government. Such a situation would be bad and perhaps catastrophic for the entire community, including the slaves themselves. A gradual emancipation would allow for more effective transition of slaves to fully engaged community members. This would benefit everyone, including the slaves. At least, advocates argued this.

Thomas Jefferson had written in 1774 that the first step to ending slavery was eliminating the slave trade. For states enacting gradual abolition laws, the first step was ending hereditary slavery and converting slaves to indentured servants. Ending hereditary slavery by itself would gradually lead to the end of slavery overall, provided states also banned importation of slaves.

1783 – Massachusetts Abolishes Slavery

In 1780, Massachusetts adopted a state constitution. In that constitution was the following language.

All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.

This language would seem to directly challenge the institution of slavery. If “all men are born free,” then they certainly cannot be born slaves. If they are equal, no one should be able to hold slaves.

Slavery was legal in Massachusetts prior to this constitution, but the legality of slavery was in doubt under this constitution. Massachusetts courts, rather than the legislature, ultimately settled the question.

Elizabeth Freeman

In 1781, Elizabeth Freeman (or Mum Bett), and another slave filed a freedom suit against their owner, John Ashley. Freeman said a public reading of the Declaration of Independence inspired her to go to court. Her attorney, Theodore Sedgwick, argued that the language in the Massachusetts constitution effectively abolished slavery. The Court of Common Pleas heard the case in August 1781. The slaves won the case, and the court ordered Ashley to pay damages of 30 shillings, plus court costs. Ashley appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court in Massachusetts. He withdrew the appeal before the court heard it because of rulings in the Quock Walker cases.

Quock Walker

Quock Walker was born into slavery. James Caldwell bought him in 1754. After James died, his widow married Nathaniel Jennison. Within a few years, she died, and Walker became Jennison’s property. The Caldwell couple had allegedly promised Walker his freedom, but that never came. In 1781, Walker escaped and went to the Caldwell house.

In the process of recovering Walker, Jennison beat him severely. Three trials came out of this incident.

Civil Trials

Two civil trials were held in the Worcester County Court of Common Pleas. Walker sued Jennison for assault and battery. He claimed that he was a free man because of a promise of freedom three years earlier. Walker won this trial. The jury found him to be a free man and awarded him £50 in damages. Tried in the same court, Jennison sued Caldwell for encouraging Walker to run away. Jennison won this trial and was awarded £25 in damages.

The losing parties in both cases appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court. Jennison failed to appear for his appeal, so he lost. The Caldwells won on the argument that the Massachusetts constitution guaranteed freedom and equality for all.

Criminal Trial

The third case was a criminal case for assault and battery. This case was tried in the Supreme Judicial Court. Chief Justice William Cushing presided over the trial. Cushing instructed the jury that slavery was unconstitutional in Massachusetts. Cushing instructed the jury to consider Walker a free man in deciding whether or not Jennison was guilty of assault and battery. Jennison was convicted and fined 40 shillings.

In his trial notes, Justice Cushing wrote the following.

As to the doctrine of Slavery and the right of Christians to hold Africans in perpetual servitude, and selling and treating them as we do our horses and Cattle, that, (it is true) has been heretofore countenanced by the province Laws formerly, but no where is it expressly enacted or established. It has been a usage — a usage which took its origin, from the practice of some of the European nations, and the regulations of British Government respecting the then Colonies, for the benefit of trade and Wealth.

But whatever sentiments have formerly prevailed in this particular or slid in upon

us by the Example of others, a different Idea has taken place with the people of America more favorable to the natural rights of Mankind, and to that natural innate, desire of Liberty, with which Heaven (without regard to Colors, complexion or Shapes of noses features) has inspired

all the human Race.And upon this Ground, our Constitution of Government, sets out by which the people of this

Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, sets out with declaring that all men are born free and equal and yet every subject is entitled to Liberty, and to have it guarded by the Laws, as well as Life and property — and in short is totally repugnant to the Idea of being born Slaves.This being the case I think the Idea of Slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational Creature, unless it his Liberty is forfeited by Some Criminal Conduct or given up by personal Consent or Contract.

(Paragraph breaks added, abbreviations expanded, some spelling and grammatical features updated to modern English; emphasis added)

Slavery did not suddenly disappear from Massachusetts as a result of this ruling. After this ruling, however, slaveholders could count on Massachusetts courts to rule against them. The period of legally sanctioned slavery was over as far as Massachusetts law was concerned.

1783 – New Hampshire Constitution and Slavery

The 1783 New Hampshire Constitution contains language very similar to that used by Massachusetts courts to end slavery there. The record is much less clear in New Hampshire.

The constitutional language provided that “all men are born equal and independent.” Further, they all have rights, “among which are enjoying and defending life and liberty.” There is not a judicial record in New Hampshire showing that courts interpreted this as abolishing all slavery. The language does seem to end hereditary slavery. This would result in slavery withering away over time, as with the gradual abolition laws enacted by some states.

1784 – Connecticut Passes Gradual Abolition Act

At the time of the American Revolution, Connecticut had the most slaves in New England. In fact, the majority of all New England slaves were in Connecticut. Ending slavery in Connecticut, then, posed perhaps the greatest challenge among the New England states.

In 1784, Connecticut passed a Gradual Abolition act. Children born into slavery after March 1, 1784, would be free at the age of 25 for men, or 18 for women. In other words, they would be fully free at the age of majority (adulthood). This Act aimed exclusively at hereditary slavery. Since Connecticut had abolished the importation of slaves in 1774, it was solidly on a gradual emancipation path.

Additional laws through the 1790s reduced the age at which these people would be free. These children were in a somewhat peculiar state. They were not considered property as their parents had been, yet they were not fully free either. Instead, they seemingly had a period of indentured servitude until adulthood.

1784 – Rhode Island Gradual Abolition Law

Rhode Island had attempted to act against slavery in 1652. In that year, Rhode Island passed a law banning slavery and periods of indentured servitude over ten years.

Whereas, it is a common course practiced amongst English men to buy negers, to that end they have them for service or slave forever: let it be ordered, no blacke mankind or white being forced by covenant bond, or otherwise, to serve any man or his assighnes longer than ten years or until they come to bee twentie four years of age, if they be taken in under fourteen, from the time of their comings with the liberties of this Collonie.

(original spelling and punctuation preserved)

This law, the result of Quaker lobbying, was largely ignored, however.

1784 Gradual Abolition Law

In 1784, Rhode Island passed its version of a gradual abolition law. Like Connecticut’s it proclaimed slavery “repugnant” to the natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Anyone born in Rhode Island on or after March 1, 1784, was free. It declared that “all Servitude for life, or Slavery of Children, to be born as aforesaid, in Consequence of the Condition of their Mothers, be, and the same is hereby taken away, extinguished and for ever abolished.” Legal hereditary slavery ended in Rhode Island on March 1, 1784.

The act went on, noting that it is necessary for the children to stay with their mothers after their birth. Since the mothers were still slaves, the law required masters to support the children until the age of 21 for boys or 18 for girls. Town Councils were empowered to help financially support these children. The law also empowered the councils to provide education for them, including placing them in apprenticeships, from the age of one year until they reached adulthood. The law further provided that slaves who were freed by their masters after passage of the law had access to the same government support as paupers.

1787 – Northwest Ordinance

Articles of Confederation

At the beginning of 1787, the U. S. Constitution had not yet been written and adopted. The United States was governed under its “first constitution,” the Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1778.

In 1778, there was not a firm sense of an American national identity. The former colonies were all states with a common cause of defeating the British in the Revolutionary War. Real power rested with the states. The Confederation was often teetering on collapse because of lack of support from member states. Strong objection to any action from even a small group of states often led to inaction.

The Articles of Confederation provided that

The said states hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.

The Articles of Confederation created not a national government, but rather an alliance among independent states. Very little power was vested in the confederation government. What power existed was primarily vested in a Confederation Congress. The Confederation Congress did not have the authority to eliminate slavery or end the slave trade. It was largely responsible for foreign and military affairs, minting money, and settling disputes among member states. Even at these tasks, the Confederation Congress was quite weak.

Westward Expansion

In 1787, the Confederation Congress was confronted with how to manage expansion of the United States to the west. The Northwest Ordinance aimed to manage part of this by creating and organizing the Northwest Territory. The Northwest Territory included the territory of the United States northwest of the Ohio River. The Mississippi River was the western boundary of the United States under the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The northern border of the country was the border with Canada.

The Northwest Ordinance organized a temporary government until the territory could be divided into three to five states. Ultimately, the Northwest Territory became the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

The ordinance explains how the territory will be governed, provides details about the organization of the territorial government, etc. Section 14 of the Northwest Ordinance provides for “articles of compact between the original States and the people and States in the said territory…”

Slavery in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Ordinance is an important historical document to consider. For our purposes, it is Article 6 of these articles of compact which is most significant.

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted: Provided, always, That any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service as aforesaid.

The states carved out of the Northwest Territory were to be free states. Indentured servants or slaves could not, however, become free simply by getting into the Northwest Territory. Instead, they would be subject to being captured and returned to their masters.

The states of Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Wisconsin (1848), and Minnesota (1858) were all admitted to the Union as free states. Though the Confederation Congress was powerless to abolish slavery, they did block its expansion in the Northwest Territory.

1787 – Constitutional Convention

Because of the great weaknesses in the Articles of Confederation, the states called a convention to propose amendments to the Articles. That convention met from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Rather than propose amendments to the articles, they wrote a new Constitution. The new Constitution was set to go into effect once nine states had ratified it in special ratifying conventions.

Some of the provisions of the Constitution have been alleged to support slavery, or at least anti-Black racism. We will briefly explore those claims here.

Claim: The Constitution Protects the Slave Trade

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides the following.

The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

Slaves and the slave trade are not directly mentioned here at all. The Framers of the Constitution likely went through great pains to avoid the words slavery and slaves. Instead, the Constitutional language is consistently “persons.” This bestowed even upon slaves at the very bottom of the social structure a degree of recognition as part of the human family.

This is the provision that lets states continue to set their own rules about who can be “imported” into the state. Congress was denied the power to prohibit importing slaves; however, it could (and did) regulate it.

Need for Unity Still an Issue

There was significant sentiment in the Constitutional Convention to abolish the slave trade outright. Several Southern delegations, however, strongly opposed abolishing the slave trade. As we saw in 1776, national unity in completing the task at hand (drafting a new Constitution) was paramount. Some Southern states likely would not have ratified the Constitution if the issue were pushed too strongly here.

Let’s assume, for example, that South Carolina refused to ratify the Constitution with a slave trade ban. Every other state might abandon the slave trade, yet it would have continued in South Carolina indefinitely. Southern states were not entirely happy with the language, yet they were not so incensed as to reject the Constitution. Keeping all the Southern states in the union kept them subject to future laws on the slave trade.

Given the strong sentiment, to end the slave trade, the 20 year provision was less a protection of the slave trade than an announcement of its expiration date. Perhaps the pro-slave trade interests expected political winds to shift in those twenty years. To a degree, they did, but not enough to slave the slave trade.

Claim: The Fugitive Slave Provision Protects Slavery

Article IV, Section 2, of the Constitution has the following provision.

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

This language is very similar to what we saw in the Northwest Ordinance. This provision was also an unfortunate aspect of compromise. This provision does not protect slavery directly. It does protect the interests of slaveholders as long as slavery did exist.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 enforced this provision for slaves who escaped to free states. As part of the Compromise of 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Free states had done everything they could to undermine the 1793 law to the dismay of slaveholders. The 1850 law aimed to undo what free states had done.

The 1850 law greatly strengthened the 1793 law by penalizing government officials who did not aid in recapturing slaves. It also largely set aside the right of habeas corpus for fugitive slave cases. This effectively stripped accused slaves of access to the courts to challenge claims that they were slaves.

The 1850 law seems to clearly violate Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution which provides that “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

Claim: The Three-Fifths Compromise Devalues Americans of African Descent

The three-fifths compromise is one of the most misrepresented or misunderstood provisions of the Constitution. Contrary to popular claims, the Constitution does not say that a black man is worth 3/5 of a white man. If that’s not what it says, what does it say?

Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution provides

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

The primary issue here is representation in Congress, specifically in the House of Representatives. Representation in the House of Representatives is based on a state’s population. Larger population states get more representatives than smaller population states. Who gets counted for determining the population? All free people, including blacks and indentured servants with a fixed term of indenture, are counted. Non-taxed Indians are excluded, so we aren’t including Indians living with their tribes, as opposed to ones integrated into American society. Three-fifths of all other persons are counted.

Who are the “other Persons”? These are slaves, of whatever race, though overwhelmingly Black – again using language referring to slaves, but not ever using the term. Why only count three-fifths of them? The bigger question was why count them at all?

Elbridge Gerry at Constitutional Convention

Elbridge Gerry was an anti-slavery delegate from Massachusetts. He observed, “Blacks are property and are used to the southward as horses and cattle to the northward.” Gerry is not claiming that blacks are property, but rather that those in the south believe them to be. He asked, if blacks in the south are treated like horses and cattle, shouldn’t we count the horses and cattle in the north?

Gerry’s argument is really this. If the South excludes a class of people from participation in government, they should not be count these people for representation in the national government. His argument has merit. We should be consistent, he suggests, in whether or not we regard these people as members of the community. If we regard them as property, then we do not regard them as members of the community.

The Southern delegations wanted slaves counted the same as free people.

Impact on Representation

Imagine you have two states. One has 1,000,000 free Persons. The other has 700,000 free persons and 300,000 slaves, should they have the same representation in Congress? Both have a population of 1,000,000. The Southern delegations argued yes, the representation should be that same. Abolitionists would argue that the first state counts with a population of 1,000,000. The second counts as 700,000, giving the slave state only about 70% of the representation of the free state.

The three-fifths provision was a compromise. Under the three-fifths rule, the population of the free state counts as 1,000,000. The population of the slave state counts as 880,000. Counting slaves as three-fifths was not a statement about the value of the person who was enslaved. It was a penalty against the slave states who held them as slaves. If the representation rules counted slaves as zero, the Constitution would have applied the maximum penalty here against the slave states.

Counting slaves as equal for representation purposes to free people did not have enough support to win. Completely excluding them was also not going to get acceptance at the convention. Counting slaves as less than free people for determining representation did not support slavery or racism. The Constitution’s method of counting population for apportionment punished slave states – as many in the convention intended.

Claim: The Electoral College Protected Slavery

Representation in the electoral college is based on the representation in Congress. The argument here follows along the lines of the three-fifths compromise and is equally of no merit.

1788 – Constitution Ratified

New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution. The Confederation Congress received word of that on July 2, 1788, and the new Constitution was now in force.

It is worth summarizing what happened between the Declaration of Independence and the ratification of the Constitution.

- six of the thirteen states either outright abolished slavery through legislative or constitutional language or passed laws to end hereditary slavery, thus adopting a gradual emancipation model to end slavery

- the Northwest Ordinance blocked slavery from expanding into what was then the Northwest corner of the country

- Constitutional language effectively reduced the political power of states with large slave populations

- Constitutional language essentially declared an expiration date for the slave trade

More States Legislate Against Slavery

1799 – New York passes Gradual Abolition Law

In 1799, New York joined the list of states passing laws to abolish slavery. Governor John Jay signed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. New York’s law followed the general pattern we have seen for gradual abolition since Pennsylvania’s law in 1780.

Persons born to slave mothers on or after July 4, 1799, were free. They were, however, indentured to the mother’s master until reaching the age of 28 for males or 25 for females.

1804 – New Jersey abolishes slavery

New Jersey’s Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1804 followed New York’s pattern. Children born after July 1, 1804 were free once they reached the age of 25 for males or 21 for females. Some states prohibited selling slaves entitled to freedom under their gradual abolition laws. In New Jersey, it was not uncommon for New Jersey slaveholders to sell slaves born after 1804 to slaveholders in slave states. This was a significant loophole that cost some people their freedom.

1808 – Slave Trade Outlawed

Slave Trade Act of 1794

On March 22, 1794, George Washington signed the Slave Trade Act of 1794. This law prohibited the building or provisioning of ships used for the slave trade in American ports. Violations of the act were punishable by seizure of the offending ship.

Slave Trade Act of 1800

On May 10, 1800, President John Adams signed the Slave Trade Act of 1800. This Act prohibited American citizens or residents from participating in the slave trade.

Slave Trade Act of 1803

On February 28, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson signed “An Act to Prevent the Importation of Certain Persons into Certain States, Where, by the Laws Thereof, Their Admission is Prohibited.” This law prohibited importing any person of color as a slave into any port in any state that had outlawed the importation of slaves. This gave the support of federal law to state laws outlawing the importation of slaves.

In his annual address to the nation in December 1806, President Jefferson said

I congratulate you, fellow-citizens, on the approach of the period at which you may interpose your authority constitutionally, to withdraw the citizens of the United States from all further participation in those violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country, have long been eager to proscribe.

The time for an end to the slave trade was drawing near.

Final Abolition of Importation of Slaves

On March 2, 1807, Jefferson signed the “Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves.” The law became effective January 1, 1808, the earliest date allowable under the Constitution.

The domestic slave trade continued. Some in Congress had incorrectly assessed that the end of the importation of slaves would doom slavery in the South. It did not. Though the slave trade was illegal, there were those who violated the law, as with any law. Smuggling continued to bring some slaves into the United States.

Increasing Penalties for Slave Trade

The 1820 Piracy Act provided, in part, that

if any citizen of the United States, being of the crew or ship’s company of any foreign ship or vessel engaged in the slave trade, or any person whatever, being of the crew or ship’s company of any ship or ship’s company of any ship or vessel, owned in the whole part, or navigated for, or in behalf of, any citizen or citizens of the United States, shall land, from any such ship or vessel, and on any foreign shore, seize any negro or mulatto, not held to service or labour by the laws of either of the states or territories of the United States, with in tent to make such negro or mulatto a slave, or shall decoy, or forcibly bring or carry, or shall receive, such negro or mulatto on board any such ship or vessel, with intent as aforesaid, such citizen or person shall be adjudged a pirate; and on conviction thereof before the circuit court of the United States for the district wherein he may be brought or found, shall suffer death.

Participation in the slave trade was now punishable by death. The law had a sunset provision allowing it to expire after a couple years. Congress made the law permanent in 1823.

In his state of the union address in 1823, President James Monroe advocated making engaging in the African slave trade an act of piracy throughout Europe. Monroe charged American diplomats in Europe with advocating that position on behalf of the United States. Note that the United States was now taking the lead in working to end the world slave trade.

Conclusions

Slavery Divisive not Unifying

What we see in the founding period of United States history is far from an organic endorsement of slavery. In some ways, the British colonies were the spearhead in the West against slavery. This began at the very time that other colonists were establishing the institution of slavery. The introduction of slavery in British North America was quite effective at breading abolitionism from the beginning.

The most prominent leaders of the American Revolution knew that slavery had to go in order to realize the ideals of the revolution. Slavery did not generally fit in the founding period. Even prominent slaveholders in the revolutionary movement – like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson – knew it.

Yes, slavery did exist, but slavery never was something upon which the United States was built. It was a counter-current to the ideals of the American Revolution. To be sure, slavery had its advocates and defenders in this period. This is why slavery was, from the beginning, a highly divisive issue.

The first six presidents of the United States all sought the day slavery would end. Andrew Jackson, elected in 1828, was the first Democratic-Republican (now Democrat) president, and the first pro-slavery president.

Lost Opportunities?

The Founding Period saw moves toward abolition by several states within a few years of the Declaration of Independence, even in the midst of the Revolutionary War. We see Constitutional provisions that consciously reduce the political power of slave states. The Constitution set an expiration date for the slave trade.

It is tragic that some of the apparent momentum for abolition in the founding period was ultimately blunted. Peaceful proposals to end slavery more quickly, such as the federal government buying the freedom of slaves, were not implemented. Pro-slavery interests, particularly in the South, consolidated and strengthened (especially with the switch to cotton as a cash crop). Abolitionist sentiment in the North strengthened also.

Slavery and Racism

We must also note that abolitionist movements did not all see Blacks as equal. Racism was a significant feature of the founding period. Even that was not a founding principle, as evidenced by race not appearing at all in the key national founding documents.

It is an interesting question as to which came first, racism or slavery. Thomas Sowell has argued that slave traders may have selected Africans not because of their race, but rather because of their availability. Slavery was an entrenched practice in much of Africa. This made it easy for European slave traders to buy slaves from willing African tribes. Once the use of African slaves was established, racism was a convenient way to justify slavery. At this point, racism and slavery then become mutually reinforcing.

Why Does this Matter?

It is a common refrain from certain segments in the United States that slavery was central to founding the nation. Given that, they argue, the United States, at its core, is fundamentally, and perhaps irreparably, flawed. This leads to contempt for the nation and all of its institutions.

Even if slavery had been a founding principle, the argument for the country being irreparably flawed may not be true. American culture could have evolved away from that.

If slavery was divisive from the beginning and not “part of the American DNA,” we must critically examine today’s problems, rather than uncritically attribute them to racism or the legacy of slavery. If this was always a divisive issue, we really must look to address issues with the legacy of slavery or perceived racism differently.

We need to deal honestly with today’s issues

Today, there are racists espousing abhorrent views, yet not everything bad in society is the result of racism. There are differences in outcomes for different groups in society, yet not all differences are the “legacy of slavery.”

It is fundamentally lazy and intellectually dishonest to say the United States was founded on slavery. It is even more dishonest to attribute today’s issues to an institution outlawed over 150 years ago. While we must learn from history, we must not remain stuck in history. We cannot continue to reflexively blame the ghosts of the past and expect to build a harmonious, prosperous future. To solve problems of today, we must do the work to accurately identify their causes. That is the only way to solve the problems of today. We owe that to ourselves and to our nation.